Pong Theology: Or Why God Doesn't Change

Why modern approaches to the Bible often lead to a mutable God

According to Genesis 6:6, God regretted making mankind, and so he had a change of mind: “And the Lord regretted that he had made man on the earth, and it grieved him to his heart” (Gen 6:6). Given the straight-forward nature of this verse, it may surprise some today to know that virtually all Christians have affirmed that God by nature does not change. He is immutable.

Largely, this conclusion follows from two premises. First, other Bible passages make the opposition assertion, namely, that God does not change: “I the Lord do not change” (Mal 3:6; also Num 23:19; 1 Sam 15:29; Ps 102:25–27; Heb 13:8; Jas 1:17). Second, reflection on God as the Bible and nature reveal led theologians to affirm God’s immutable nature.

Today, however, some have challenged the earlier consensus that God does not change due to passages like Genesis 6:6, a philosophical rejection of classical theology, and a suspicion of nature theology.

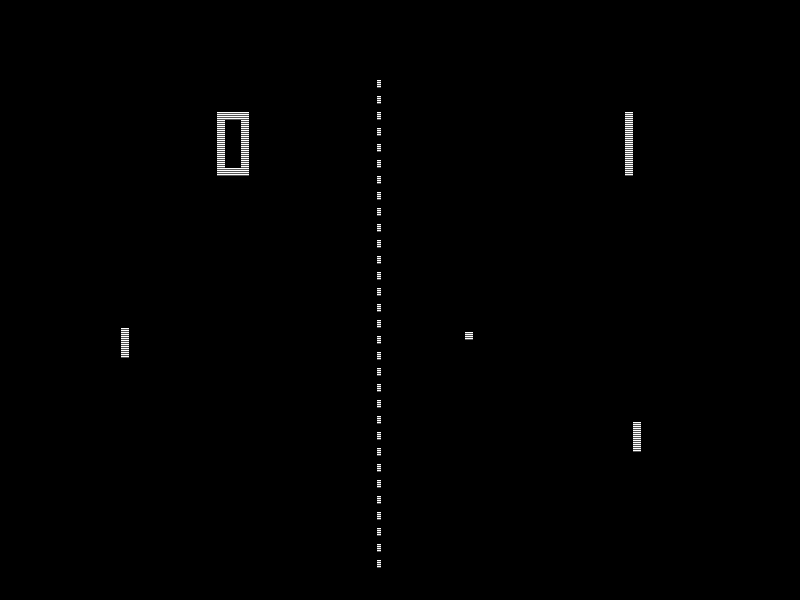

While I do not plan to explain why various groups aim to affirm something mutable in God, I would like to point out how some attack and defend the doctrine today. The method used by many on both sides of the debate can be called pong theology. It bounces between Bible verses that affirm and deny that God changes until there are no more passages. The result is a synthesis, but one that underdevelops the reality that God is in place of a series of signs.

Put more formally, this article names the difference between (1) a Bible verse shock-and-awe approach to theology and (2) a reality-centred way of approaching biblical theology. The first approach often leads to a version of God’s mutability across a wide spectrum; the second approach approximates how most Christians have read the Bible and leads to classical definitions of God (e.g., his immutability).

Pong Theology

Pong theology bounces the ball of interpretation back and forth over various sets of texts. It first hits Genesis 6:6 and then bounces back to Malachi 3:6. It then bounces back to 1 Samuel 15:11 before jetting across to 1 Samuel 15:29. After the ball hits each side (all the verses), it finally stops.

As it bounces to texts that say God changes, it takes that verse into its dataset. Then it bounces back to a text that says God does not change. Again, this information adds to the data. Finally, a synthesis happens. God does not change in being, one might say, but God does change in his present pleasure or displeasure towards someone or something. This is the position that Wayne Grudem takes. But others using the same method will conclude: God changes and responds to us, even though his overarching purpose does not. This synthesis of biblical data approximates an Open Theism view.

The problem with this method is that it ends up bouncing between ideas in the hopes that a synthesis will appear. But in reality, it is a game of signs. Signs signify realities, not just more signs.

But what reality are we talking about? And how do the words (signs) speak about this reality? As Augustine notes, “what matters in considering things is not what our language will or will not allow, but what meanings emerge from the things themselves” (Book 5, De Trinitate). When it comes to the question of God changing and passages like Genesis 6:6, it is essential to realize that we deal with realities, not just signs or words.

I will return to this in a moment, but let me turn to Genesis 6:6 to illustrate the point.

Genesis 6:6

Genesis 6:6 says, “And the Lord regretted that he had made man on the earth, and it grieved him to his heart.” In context, it refers to the evil of mankind who lived on the earth. It follows Genesis 5 in which we learn that all die because all sin. Apparently, Enoch stands as the exception since God directly took him (Gen 5:24).

Kenneth Matthews draws a linguistic connection between Genesis 5:29 and 6:6, which share three words: “‘comfort’/‘grieved’ (nḥm), ‘labor’/‘made’ (ʿāśâ), and ‘painful toil’/‘pain’ (ʿāṣāb).” (1:341). I would add a possible fourth word (adam/adahah). Given their proximity and linguistic relationship, both passages should be read side-by-side as they together show how “Lamech’s hope for his son as the deliverer from the toils of human sin is realized in part through Noah’s survival of the flood and his inauguration of a new world for the blessed seed.” (1:341).

Compare the two passages:

Genesis 5:29: “…and called his name Noah, saying, ‘Out of the ground (הָ֣אֲדָמָ֔ה) that the LORD has cursed, this one shall bring us comfort (נָחַם) from our labor (עָשָׂה) and from the painful toil (עִצָּבוֹן) of our hands.”

Genesis 6:6: “And the LORD regretted/grieved (נָחַם) that he had made (עָשָׂה) man (אָדָם) on the earth, and it grieved (עָצַב) him to his heart.”

Here, we have a symbolic reversal whereby God takes the grief and pain of man into himself, and thus “preserves Lamech’s lineage through Noah” (Gen 8:1; Matthews 1:341).

Contextually, then, we see an act of God’s mercy by saving or preserving Lamech’s line through Noah, bringing rest or comfort. However, this salvation comes through a deluge of judgment against a world that owes death to justice.

How then does God grieve and feel pain?

Readers have attempted to explain how God grieves and feels pain in Genesis 6:6 in various ways.

(1) We could say that Genesis 6:6 literarily aims to parallel Genesis 5:29, but that the text does not say anything about how God truly experiences human evil. So this would be a literary expression. But most people would find it insufficient because the Bible should be expected to reveal something true about God when it speaks.

(2) One could say that God changes from joy to grief and pain because of human sin. We thus affect or change God’s emotional state. Matthews does something like this when he says, “Our God is incomparably affected by, even pained by, the sinner’s rebellion. Acknowledging the passibility (emotions) of God does not diminish the immutability of his promissory purposes” (1:344). Evangelical theologian John Feinberg likewise redefines immutability and notes, “it is necessary to reject divine impassibility” (No One Like Him, 277). He speaks of Genesis 6:6 as indicating a “relational change” in God but not an essential change in God’s being (274). The disadvantage of this view is that it contradicts almost two millennia of Christian teaching and seems less sensitive to the ways in which Scripture accommodates God’s

(3) Open Theology takes this prior argument to further places by positing that the future is open to both God and us, because human beings have the freedom to choose, and God has prepared for every possibility. Applied to Genesis 6:6, Dan Kent writes: “to say that God ‘doesn’t really regret’ (as many Reformed theists say to explain away Gen 6:6) implies that every event unfolds exactly how God wants it to unfold, which is tantamount to saying: everything is the way God wants it to be. And this ultimately means God “wants” children to suffer” (Source).

But not everything is the way God wants it to be (yet), according to Open Theists, and thus human evil may be explained not by God’s providential will, which he chooses to curtail, but by human choice. Genesis 6:6, on this reading, would simply show how humans choose evil, and how it affects God, who chooses to limit his providence and allow for human freedom. Hence, Greg Boyd writes, “But [God] does not possess exhaustively definite foreknowledge, for the future he perfectly knows is not exhaustively definite” (Source). Much of the impetus in Open Theism, as represented by Clark Pinnock, John Sanders, and Greg Boyd, centres on theodicy and the argument that love requires risk. I think everyone would agree, then, that the question is not solved primarily through exegesis in abstract categories; the question involves a deeply philosophical one based on one’s view of God, human action, and realities like love, evil, and justice.

(4) Such positions have led scholars like Wayne Grudem to engage in pong theology. While Grudem recently affirmed a version of impassibility (2020), he still affirms that “God does act and feel emotions” (Systematic Theology, 192, 2nd ed.). However, he wants to avoid the straightforward admission that humans can affect God as Open Theism claims or as writers like Matthews and Feinberg appear to admit.

After all, Grudem well knows that virtually no Christians historically could have or would have affirmed God’s mutability in the ways that Matthews and Feinberg do above. Hence, Grudem finds himself only cautiously affirming immutability in terms of God’s “being, perfections, purposes, and promises” (163, 1st ed.). And he further wants to describe changes such as in Genesis 6:6 as God’s present attitude towards his creation (165, 1st ed.); a view, I should note, that feels underdeveloped given Grudem’s view of God’s timeless seeing of all things (170, 1st ed.).

Applied to a passage like Genesis 6:6, Grudem speaks of God’s regret as expressing his “present displeasure.” Grudem hopes such language protects God’s immutability. However, here, he also affirms that God feels emotion (so a sort of change), while denying that God’s purpose is thwarted (so unchangeable in purpose). In his own words:

“In the cases of God regretting that he had made man or that he had made Saul king, these should be understood to mean that (a) God felt sorrow when considering the sinful results that had come after his earlier actions, but this is still consistent with the idea that (b) God knew that these events that caused him grief would still fulfill his long-term purpose of showing his justice and holiness when he brought judgment on sinful behavior. These verses should not be understood to mean that God thought he had made a mistake or that if he could start again and act differently, he would in fact not create man or not make Saul king. The verses should be understood as expressions of God’s present displeasure toward the sinfulness of man. God’s previous actions led to events that, in the short term, caused him sorrow but that nonetheless, in the long term, would achieve his good purposes.” (195, 2nd ed.).

In other words, God chooses to feel grief and sorrow to accomplish his long-term immutable purpose. He is mutable (passible) when it comes to his emotional life, but he is immutable in his being, perfections, purposes, and promises.

Why cannot Grudem affirm, as classical confessions and Christians have done, that God is immutable in every way? The answer, I think, comes down partly to method and metaphysics. Grudem admirably cites Scripture, but bounces pros and cons back and forth across Bible verses until he synthesizes a conclusion on the basis of all that these Bible verses say. But he does not reflect on “realities” but on the textual “signs.”

Let me put it this way. Biblical words are signs that point to some real thing. The word Jerusalem is merely a sound, but since it refers to a real city, we know the word refers to a real entity. When the Bible speaks about God, it uses visible signs to point to God as an Invisible reality. Grudem, by method, bounces back and forth between signs, synthesizing the signs into a complex sign. But methodologically, he does not push through to see what these signs represent.

Passages like Psalm 102:25–27, which Grudem cites, do speak of God not changing, but Exodus 32:14 represents God as changing. So when one bounces the ball back and forth to each verse, the conclusion that Grudem and others draw is: God must change emotionally, but not in his purpose. Hence, God allows himself to feel regret to fulfill his larger designs.

The obvious problem here is: how can God grieve, feel pain, or regret, given all that we confess about him? Grief usually changes our nervous system response, our hormones, heart, and other physical traits. We cannot sleep due to this bodily disorder. Tears come from our eyes. Our hearts beat faster. Our gut drops. Pain is a biological response that we experience in our bodies.

But God is Spirit (John 4:24). What does it mean for God to feel emotions? How does God feel the passions of the flesh as we do? After all, we mean something different by emotion being embodied than God does as an Immortal Spirit. God has no sinews, hormones, veins, or electrical impulses in his flesh. So to say that God feels emotions means what exactly?

Signs to Realities

The reality that God is therefore provides the most important context for interpreting Scripture. When God says his nostrils flare, we know he signifies the reality that God is just and punishes evil. We do not imagine that God created nostrils for himself and thus literally flares them out. But had we not known who God was, is, and remains, we might be tempted to read such passages too literally.

God has always been who he is: “his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made” (Rom 1:20). And he has revealed himself in Christ, his Beloved Son, as the final Word from the Father (e.g., John 1).

We thus judge that Christ was born of a virgin in accordance with his human flesh, while remaining always the immortal and holy God that he is. This reality transforms how we read Scripture since, again, reality is the most important context of Scripture. It is more important than other essential contexts like history and grammar.

So when Jesus prays in the garden, “not my will, but yours be done” (Matt 26:39), we discern in the signs (the words) the reality that Christ is both divine (with a divine will) and human (with a human will). So he, by definition of the reality that he is, must be conferring his human will over to the divine will of the one God who is Father, Son, and Spirit. Why speak of it then? Because Christ, for us and for our salvation, handed over his human will to God; for in the form of a slave, he was obedient, even to the point of death on the cross (Phil 2:7–8).

In the form of God (Phil 2:6), he did not count equality something to be grasped, Paul informs us. But in the form of a slave, he submitted fully to his Father. And so he was even made sin so that “we might become the righteousness of God” (2 Cor 5:21).

Again, the above exegesis requires reality to be the most important biblical context through which the signs of history and grammar come into clear sight. The Bible exists in the real world. When it tells us that the sun, moon, and stars are for signs, times, and seasons (Gen 1:14), we know about the lights in the expanse prior to reading the Bible. But the Bible interprets or names that reality. The sun remains the sun, the stars the stars, and the moon the moon.

In a sense, we must know something of God prior to reading the Bible, through the preaching of the word by which we are saved, and through natural revelation. Paul affirms:

“For what can be known about God is plain to them, because God has shown it to them. For his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made. So they are without excuse. For although they knew God, they did not honor him as God or give thanks to him…” (Rom 1:19–21).

Paul’s logic here matters. People “knew God” because God showed himself to all by his creation. We can thus know “his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature.” The travesty of this knowledge is that we exchange God’s glory for created goods that God himself made! Humans can know God and even thus reject him. This is precisely why “they are without excuse.” If they did not know God, they would have no excuse; but they do know God, so they are without excuse.

Note the order. Paul says people know something of the reality that God is by natural revelation. Scriptural revelation, of course, gives saving knowledge and knowledge of the mystery of the Trinity. But even here, God’s salvation and triune nature are real. And so once we know the Gospel and God as the triune God of Scripture, we must read Genesis 1 as speaking about the Father creating through his Word when he says, “Let there be light” (Gen 1:3). There is no other referent to which the signs can point.

If we say, “But what did Moses know?” or “the words of Genesis 1 only speak of physical words,” then we fall into a double error: we fail to recognize the reality that God is—the Father, Son, and Spirit—and we also fail to think rationally, since no physical word can exist before voice boxes were created, atmosphere existed, and so on. The Word that God spoke even before creation came into being was the Eternal Word of the Father: “All things were made through him, and without him was not any thing made that was made” (John 1:3).

The signs of Genesis do not tell you this unless you know the reality to which the signs point. John does. And hence he reads Genesis 1 in a triune way.

The Reality of God in Genesis 6:6

Applied to the question of Genesis 6:6, the reality that God is must be the key context in which we interpret the signs of Scripture alongside history and grammar. Once that is realized, we might say—along with passages in which God’s nostrils flare, or his nose lengthens, or his arms are raised—that God regrets here to signify his just opposition to human sin and evil.

The alternative seems to be playing a long game of theological pong that gets us lost in a swarm of signs without ever seeing the reality that God is.

Excellent in-depth of God’s attributes of Immutability and Impassibility- both necessary for Him to be…God. The Creator is always greater than his creation- try as we might to domesticate Him.

As Stephen Charnock notes, “ Slowness to anger, or admirable patience, is the property of the Divine nature. As patience signifies suffering, so it is not in God. The Divine nature is impassible, incapable of any impair, it cannot be touched by the violences of men, nor the essential glory of it be diminished by the injuries of men...”

I hope someday someone elaborates more fully on the kind of theological thinking implied behind Paul's elliptical arguments in Acts 14, Acts 17, and Romans 1. In each case he seems to be making allusive reference to cosmological arguments, without explaining them in detail. But those kinds of arguments imply a certain kind of theism.