What is History?

Some reflections on the historical process itself, and why it matters

When we talk about history, we often mean the study of events: dates, wars, kings, and discoveries. But what if we asked a deeper question: What is history itself? What kind of process is it? What does it mean to say that history “moves,” “teaches,” or “progresses”?

These are the kinds of questions I explore in this article: not only what happened, but how we understand the happening. In another article, I will lay out my philosophy of history; this is more of a survey than an argument.

Does History Have Meaning?

If history has a telos (a purpose or goal) then we might ask whether it follows discernible laws, patterns, or causes by which it achieves that end. Some thinkers, like Hegel, saw the process of history as the unfolding of Geist (Spirit or Rationality) through time. Others, like Marx, believed that history is made by individuals and economic forces, not by Spirit.

Still others, especially within the Christian tradition, understood history as guided by divine providence: God acts through contingent human beings to accomplish his purpose. But even there, the question arises: does God enter history directly, or did he simply establish the laws that govern it, as a kind of providential clockmaker (the Deist view)?

Can We Learn From History?

Many cultures have said yes, but for very different reasons.

For the Stoics and in Vedic thought, history often moves in cycles, repeating its lessons endlessly. Others, such as Nietzsche or later historicists, wondered whether history reveals anything stable at all. Perhaps every human act is so historically conditioned that no universal truth remains, only shifting perspectives.

Others take the opposite view: that history does teach. It shows us recurring patterns of wisdom (“learn history so as not to repeat its mistakes”) or perhaps even scientific regularities. Yet even then, we must ask: why should the universe have such stable laws? What justifies that assumption?

Maybe, as Hegel argued, Spirit itself guides the process toward freedom. Or perhaps, as the Greeks believed, divine forces steer events arbitrarily. A Christian might say that God, as a personal agent, embedded rational laws (mathematical, moral, and physical) into creation so that rational creatures could discern them.

Can We Know History?

Modern thinkers like Auguste Comte, the founder of positivism, believed we could. He claimed that history could be studied as a science: observe, classify, and discover its laws, just as in physics or biology.

On that view, the rise of the scientific method in the modern West reflects a belief that history itself is rational, that events unfold according to discoverable principles.

But this raises a serious problem: if we assume that the world is rationally structured and that humans can understand it, what justifies that assumption? The scientific method itself cannot explain why the universe is intelligible or why our minds correspond to it. Aristotle saw this long ago: knowledge rests on first principles that cannot themselves be proven by method.

A Christian might say those principles come from God, who made both rational creatures and rational laws. That would explain why science, faith in reason, and the belief in order arose together in the West; yet that claim, too, must be argued.

Knowing the Past

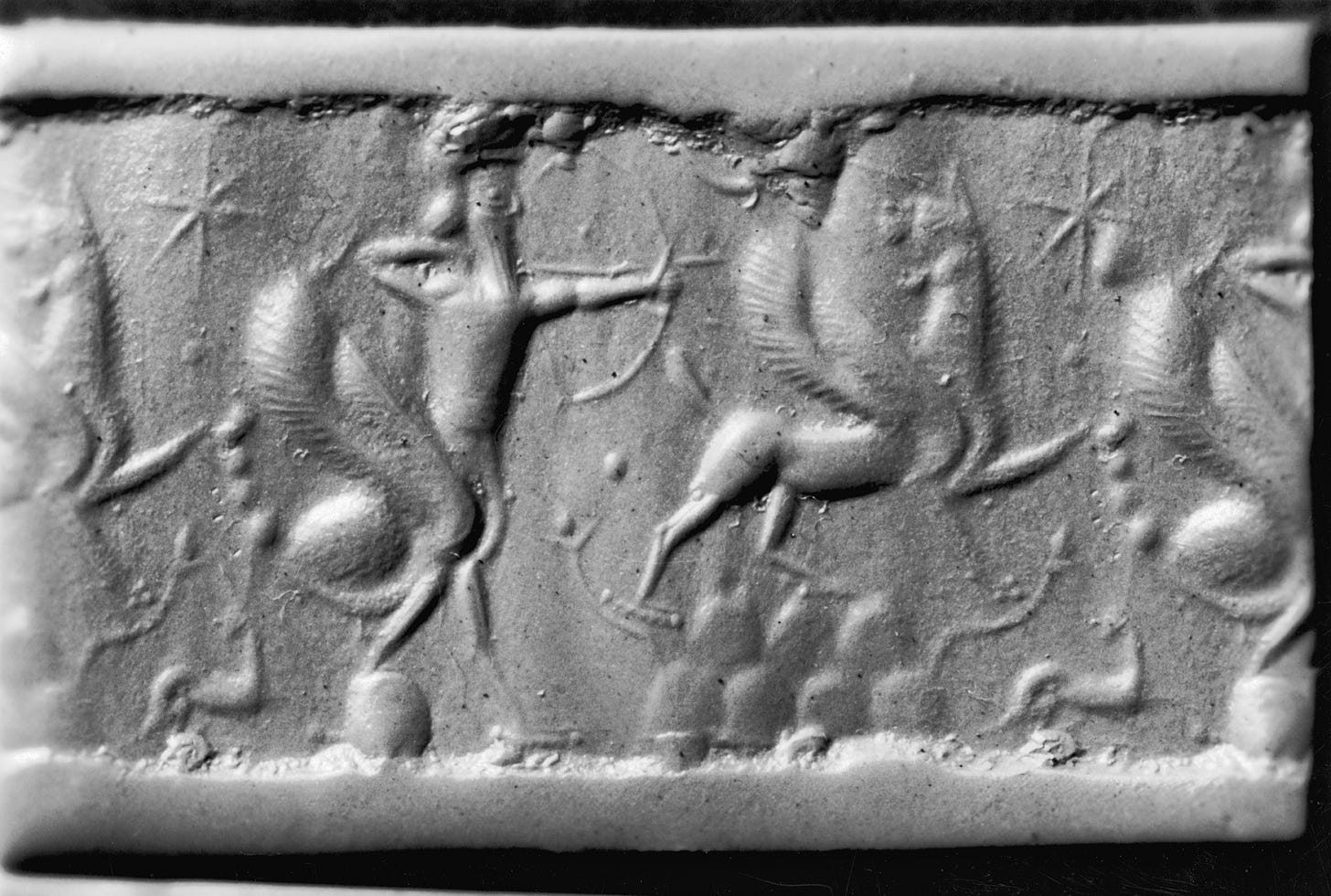

Even if we grant that history leaves artifacts (art, sculpture, writing), what is our relationship to those remains? How can we really know the people who made them?

Hegel thought that by studying historical evidence, we could trace the unfolding of Absolute Spirit toward freedom. In his view, human history reveals the logic of Spirit working itself out in time. Yet that’s a bold claim. Does the rise of European nations, for example, truly show that Spirit is moving toward freedom? Or are we simply reading our own ideals back into the record?

Many moderns assume that science guarantees progress, that we are always moving toward something better. Perhaps that’s true, but why must it be true? Without a metaphysical reason, that faith in progress becomes an unscientific article of belief.

The Hermeneutical Challenge

Now the problem grows even harder. If something happened five minutes ago, we can recall it confidently. But what about something that happened four thousand years ago?

Consider Hammurabi, king of Babylon in the nineteenth century BC. What can we truly know about his motives, his thoughts, or how his famous law code was applied? Historians can examine tablets, inscriptions, and archaeological evidence—but Hammurabi’s inner world remains closed to us.

Some nineteenth-century thinkers, like Dilthey, spoke of Verstehen, understanding the past by imaginatively “re-living” it (Einfühlung). Yet that can sound mystical or naïve. Still, what is the alternative? Much of what mattered most to ancient peoples—their symbols, hopes, and fears—lies buried in the sands of time.

And when we turn to ancient myth and poetry, such as in Gilgamesh, the Enuma Elish, or the Vedas, the task grows harder. These texts use metaphor and symbol, not straightforward prose. Their meaning is layered, elusive, and open to re-interpretation.

The Afterlife of Texts

The philosopher Paul Ricoeur once reminded readers that when an author writes, he has no reader before him; and when a reader reads, he has no author before him. The written word cannot defend itself or answer our questions. As Plato already saw in the Phaedrus, writing seems alive but does not speak in the same that a dialogue can.

Every text therefore takes on a kind of independent life. Ancient works, whose authors are anonymous or lost—like Gilgamesh or the Vedas—float free from their origins. Some are even revised by later scribes. After Sennacherib’s sack of Babylon in 689 BC, for instance, Assyrian scholars adapted the Enuma Elish to praise Ashur instead of Marduk. Such rewriting reminds us how fluid the textual past can be.

So what does it mean to interpret? Can we simply apply a method, as in science, to recover an author’s intent?

Understanding, Not Just Method

Hans-Georg Gadamer didn’t think so. Drawing on Martin Heidegger, he argued that understanding is more than applying the right technique. It is a dialogue between past and present—a “fusion of horizons” where the world of the text and the world of the reader meet within the continuity of tradition.

Ricoeur agreed but added another insight: once written, a text gains distance from its author. It becomes autonomous, open to new interpretations. Reading is therefore an act of self-understanding; the reader is changed by the world that the text opens. (I have some important criticisms of this method, but that is for another time).

These approaches may sound unscientific, and in a sense, they are. They remind us that human understanding is not the same as a laboratory experiment. Modern science seeks explanation and organization; humane hermeneutics seeks explanation and understanding.

The past becomes knowable not through mastery of technique but through an interpretive encounter, a kind of conversation across time. I do not believe, however, that textual meaning is somehow entirely subjective or that the author’s intent cannot be reasonably discerned. I only note that we have historical limits that prevent us from being overly confident about certain aspects of the past.

In Conclusion

When we ask What is history? we enter a web of questions.

Metaphysical: Does history have a purpose? Is there providence, fate, or progress?

Epistemological: Can we know history scientifically, or does it rest on faith in reason itself?

Hermeneutical: How do we understand the texts and traces the past leaves behind?

History, then, is not simply a record of events. It is an ongoing dialogue between past and present, between what was and what we can still make sense of. To study history is to enter that dialogue, to discern what it true and good, and to let it change us.

Addendum

I will have much more to say about this at a later time, since I believe we can discern objective truth in history because God has embedded natural laws into his creation. Here, I want to survey the questions around history itself without saying much about my positive view. So for now, I will cease to write!

Looking forward to more, Wyatt.

In my experience here in Australia, history is so often taught and written from a Left wing perspective, going right back to my state school days.