What Does Job Repent of?

The answer depends on a Hebrew word we may be mistranslating

At the end of the book of Job, after thirty-seven chapters of argument, accusation, and anguish, Job says something that has confused readers for millennia: “I despise myself, and repent in dust and ashes” (Job 42:6). Some readers take this as a confession, namely, that Job finally admits that he was wrong, that his suffering was deserved, that his friends were right all along.

But that reading has a serious problem. It puts us on the side of Job’s three friends. And the whole book of Job aims to deny their viewpoint, stemming from the principle of retribution (i.e., you get what you deserve).

So if that is not what Job means, then what does Job repent of? That is what this article seeks to answer. To answer that question, we need to begin with Job’s three friends who accuse Job of suffering because of sin.

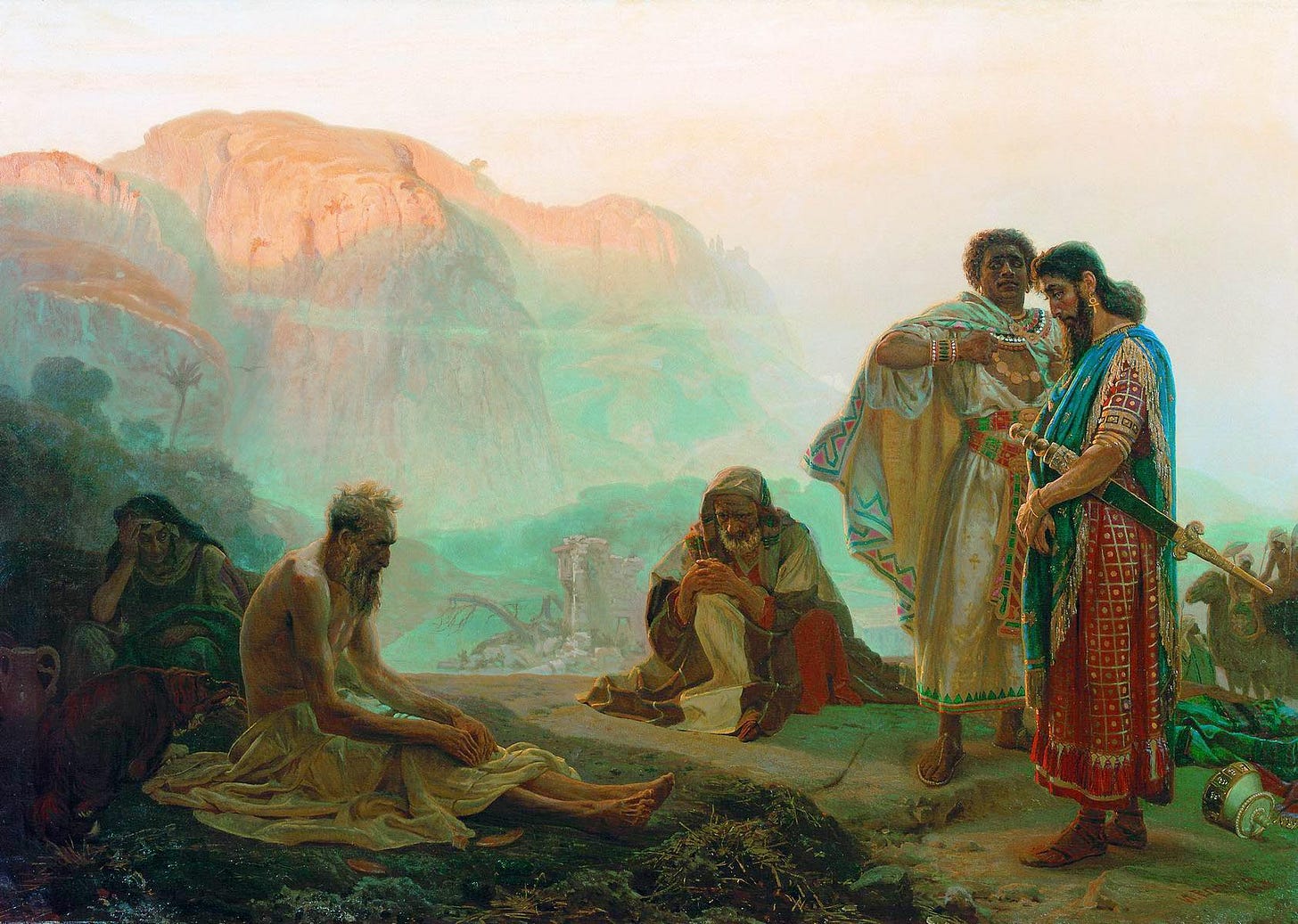

Job’s friends accuse him

Job’s three friends (Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar) accuse him of sin. Their argument is simple: suffering is punishment; therefore, Job must have done something to deserve it. Repentance is what he must do. But we as readers know that Job is innocent, because God himself declares it.

In the book’s prologue, God says of Job: “There is none like him on the earth, a blameless and upright man” (Job 1:8; cf. 2:3). And at the very end of the book, God rebukes the friends directly: “You have not spoken of me what is right, as my servant Job has” (Job 42:7–8). In other words, Job is upright and speaks rightly.

A fourth friend, Elihu, enters the dialogue in Job 32–37 and accuses Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar of failing to find an answer, even though they declared Job guilty. He also accuses Job of vindicating himself rather than vindicating God. Elihu thus aims to vindicate God on God’s behalf.

As I will explain below, God does not appear to want or need Elihu to do so, placing Elihu’s words as a failed attempt to take control of Job’s situation by over-reading his theology and thus denying the mystery of God’s Being.

Job’s desire to plead his case

Although Job’s friends accuse him, Job does not cave. Throughout the dialogues, Job insists that if he could only stand before God, he could vindicate himself. He is confident that he could argue his case and be declared innocent:

“But I would speak to the Almighty, and I desire to argue my case with God” (Job 13:3).

“Though he slay me, I will hope in him; yet I will argue my ways to his face” (Job 13:15–16).

“Behold, I have prepared my case; I know that I shall be in the right” (Job 13:18).

“Oh, that I knew where I might find him, that I might come even to his seat! I would lay my case before him and fill my mouth with arguments” (Job 23:3–5).

“There an upright man could argue with him, and I would be acquitted forever by my judge” (Job 23:7).

“Oh, that I had one to hear me! Here is my signature! Let the Almighty answer me!” (Job 31:35).

Job wanted a day in court with the Almighty. He got one. But when God speaks from the whirlwind, he does not invite Job to present his case. He turns the tables: “Who is this that darkens counsel by words without knowledge? Gird up your loins like a man, I will question you, and you shall declare to me” (Job 38:2–3).

God answers from the whirlwind

After 35 chapters of silence, God finally speaks to Job (Job 38–41), but God does not answer Job in ways we might expect. He does not explain Job’s suffering, nor does he adjudicate the dispute between Job and his friends.

God simply reveals himself: his power, his wisdom, his transcendence. His speech harkens back to Job 28, the key chapter of the book, which argues that human beings cannot find wisdom because only God knows where it dwells.

The implied critique cuts in every direction. Job’s three friends have not found wisdom. And Elihu, too, is silently rebuked for presuming to vindicate God when God needs no human advocate. A mortal cannot possess the wisdom that belongs to God alone (Job 28).

God’s answer, in the end, is simply: I am who I am. And the I that I am transcends you. There is no explanation that human words can give. And God needs no advocate to vindicate him. Job came to realize this when the wonder of God confronted him from the whirlwind.

What Job repents of

So when Job sees who God is, he can only say: “I have uttered what I did not understand, things too wonderful for me, which I did not know” (Job 42:3).

This is what Job repents of. Not sin or moral wrongdoing. Instead, Job repents of having spoken about God ignorantly, of having presumed to comprehend the grandeur and wonder of a God who transcends all human categories. God himself affirms that Job did not sin. But Job did speak beyond his understanding.

For this reason, Job says, “I despise myself, and repent in dust and ashes” (Job 42:6).

Or does he say this?

It is important to recognize that the Hebrew of Job 42:6 is not easy to translate, and the familiar rendering given above may not be the best one. Another possible translation is: “I reject and am comforted in/concerning dust and ashes.”

If this is the correct translation, the passage could mean one of two things. First, Job could be rejecting the posture of mourning, having been comforted by moving past dust and ashes (symbols of grief) and now turning to the blessing that would mark the next phase of his life (Job 42:7–17). Gignilliat and Thomas thus paraphrase the passage, “I reject and I am comforted regarding the mourning process I have undergone. I can now move to a renewed sense of life” (2025: 302).

Second, he could be rejecting his anxiety about mortality and rejecting his belief that his suffering meant that God rejected him. In Job, “dust and ashes” generally refers to human mortality, echoing the language of Genesis, where Adam is made from the dust of the ground. The Hebrew preposition ‘al in the phrase usually translated “in dust and ashes” does not typically mean “in” but rather “concerning” or “about.” That Job likely takes comfort concerning dust and ashes furthers the sense that the traditional English rendering of Job 42:6 may not capture Job’s words fully.

Putting this all together, we can say: because Job rejects his previous opinion on dust and ashes, he takes comfort. In Job’s last speech, he lamented that God had hurled him into a clay pit. He had become like “dust and ashes” (30:19; cf. 2:8) before a God who has rejected him (30:20–23).

On this view, Job’s confession is that he was wrong about God. God had not rejected him. Actually, Job spoke unwisely, believing that his innocent suffering could only mean that God’s smile had turned to a frown (29:1–6). Job’s confession too, then, follows the same lines of thought that Job 28 does. Human wisdom fails before the creator God’s wisdom; Job was wrong about God’s rejection of him, and he must fear God and turn from evil (28:28).

The point stands either way

However one takes Job 42:6, the conclusion remains the same. Whether we call it repentance or comfort, the theological point is the same. Either way, God vindicates Job’s innocence (Job 42:7–8), just as we knew from the beginning (Job 1:8; 2:3).

To read the book of Job as a story about a man who suffered because he sinned is to agree with his three friends. But the entire book denies that proposition. The narrative denies it. God himself denies it. We should too.

And so we cannot read Job 42:6 as a confession of the sin that caused his suffering, unless we wish to say that speaking beyond one’s understanding constitutes that sin (Job 42:3). Even then, that would not be the sin that caused his suffering. It would be the sin, if we may call it that, of having tried to comprehend a God who is beyond comprehension.

The vindication of Job

The principle of retribution in the ancient world led Job’s friends to claim that Job suffered because he sinned. But the narrative framing of Job (Job 1–2) and God’s own comments in Job 42 vindicate Job and condemn his friends:

“After the Lord had spoken these words to Job, the Lord said to Eliphaz the Temanite: ‘My wrath is kindled against you and against your two friends; for you have not spoken of me what is right, as my servant Job has. … my servant Job shall pray for you, for I will accept his prayer not to deal with you according to your folly; for you have not spoken of me what is right, as my servant Job has done.’” (Job 42:7–8)

Job spoke rightly of God. Job was innocent. His problem was one of experiential knowledge, of speaking of things too wonderful. He was formally correct in his words, but he could not know that his human words and ideas could not comprehend God in all his majesty. Only when God revealed himself to Job in the whirlwind did Job know.

We find no answers to Job’s suffering except what Job 28 has already told us. Humans cannot find wisdom on their own. Instead, “Truly, the fear of the Lord, that is wisdom; and to depart from evil is understanding” (Job 28:28). This, and this alone, is what mortals can grasp. God’s ways are too far beyond our reach.

And perhaps there is comfort in this. We cannot always explain why we suffer. To do so, to take control by explaining it away, would be to follow Job’s friends in their retributive principle or to follow Elihu in his claim to speak on behalf of God. Instead, we have to cast ourselves wholly into the God who is beyond our comprehension. We must commit our ways to him, and allow the fear or awe of God to be our beginning of wisdom.

Thank you for these insights and reminders.