The Disappearance of Natural Law in Technological Society

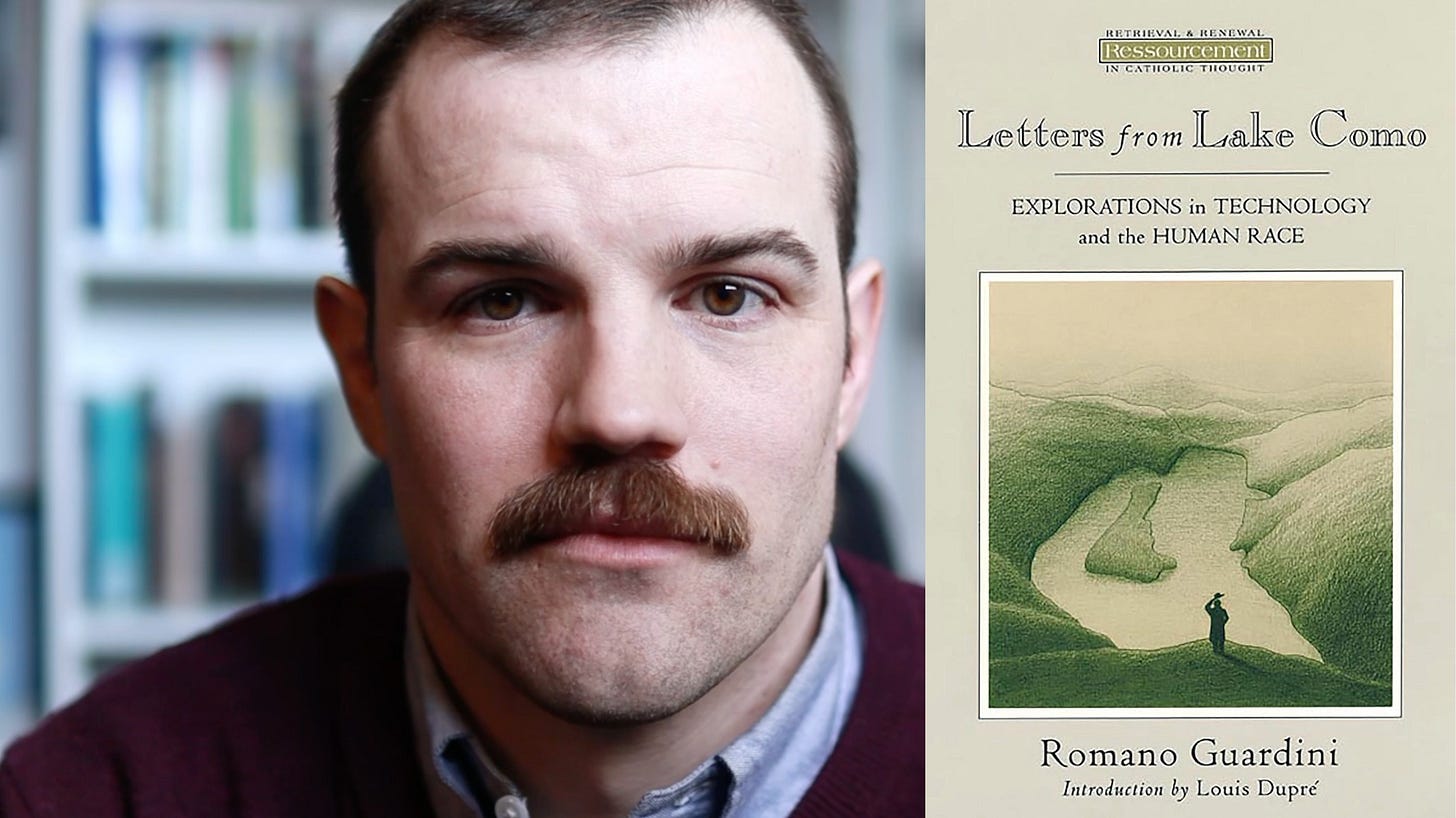

Romano Guardini and the loss of organic culture

Romano Guardini, in his Letters from Lake Como, contemplates the cultural costs of modern technology. What we lost, he suggests, is a relationship between culture as an organic expression of nature, that slowly, over time, conforms itself to the natural contours of the world around us, and only then, gradually, reshapes that nature in return. Instead, industrialization has changed how we relate to nature.

In particular, Guardini sees us now living in a machine-like society. Instead of organically relating to nature around us, we come to dominate it through factories, manufacturing, and industrial means and thus reshape the environment in which we live.

Guardini came to this realization while travelling from Germany southward to Italy. In the places he stayed, he found a human culture more organically related to the land than the factories and machines he had left behind in northern Europe, which orchestrated everything towards machine-like ends.

The abstraction of technological society

Guardini makes several interesting observations, but the one I want to highlight here is this: mass society, or what we might call technological society today, creates a culture that relates to nature in a way that is remote, abstract, and further removed from nature than in centuries past.

No longer do we look at a river and build a bridge at its most narrow, most obvious, or most humane point. We command our motors against the current more than we float down the river on sailing ships under the command of the wind. Instead, as Martin Heidegger observes in his essay “The Question Concerning Technology,” we build hydro dams to extract power. We create tour guides to present the river as something to be viewed. We build bridges wherever we want for economic or material advantage. We use technology to dominate and master nature.

Now, human beings have always done something like this. But the way we have taken dominion over nature in the past is not the same as it is today. The mechanical machine age and mass society of the mid-twentieth century, and now the technological age in which we live, do something rather strange: we enframe the world as a resource to exploit, control, and count. We use mechanical and technological means to master it for our own chosen ends.

We have bridges, trains, cars, and planes; these are the modern mechanisms of society that control and shape everything. We no longer rely as much on the contours of the land itself, only slowly and incrementally building a culture out of it. Technological society today, mass society of the mid-twentieth century, and machine society of Guardini’s time represent modes of increasing abstraction and removal from a close and intimate relation to the land around us, to the geography in which we live.

What technology does to us

What does this mean for us? Guardini says it changes us.. We don’t always know how it changes us, but it transforms how we think of the world and the people around us.

Everyone senses this at some level. In the technological age, we are wired to mediate experience through technology, through phones. We fail to see each other face to face, not confidence in unmediated encounters. The world seems more digitally friendly. Friendships are cultivated more through chat rooms and social media than fireplaces and laughter. It represents a fundamental change in who we are as human beings, how we relate to the world around us, what we expect, what we assume, and how we feel about the world.

Most people in cities don’t know how to replace an o-ring on a toilet or cook an omellete for breakfast. Instead, we call the plumber; or we use DoorDash. In this regard, we have so altered our relationship to food that we order meals prepared by others, despite the fact that it costs much more than preparing them ourselves. And we lose thereby an organic connection with the food we have grown or purchased and made for ourselves.

The alienation of human culture

This transformation happens across all of society and changes the kind of culture we create. When culture was necessarily bound to the land and to the limits that geography and space imposed upon us, we would grow culture little by little to bring order to the land around us in a way that was in agreement with the land. A windmill required wind to turn it in order to crush grain. Now we use machinery and electricity extracted from the wind, rivers, the sun, or whatever source is available. It changes our entire way of thinking about enculturation.

Human culture now is an abstracted culture, alienated from the world around us through our advanced technological means.

As C.S. Lewis observed in The Abolition of Man, as we come to dominate more and more of nature, nature itself becomes something that dominates us more and more because we become like the thing we are dominating. In other words, as Heidegger observed, when human beings see the world as something to be counted, calculated, ordered, and held ready as a resource to be used, rather than an organic, natural world that reveals itself to us, we begin to see ourselves as a kind of human calculator. Everything requires an Excel spreadsheet. Nature is ours to order, count, optimize, and put into place, just like the machinery we use to organize the nature we now view as a machine.

The loss of natural law

I don’t know what the final result of all this will be, but I will say that it makes me more aware of one key moral point I want to outline as I finish this reflection.

In prior societies, when you were necessarily closer to nature, you created a culture that was organically related to it, even as you ordered the nature around you. But in a culture today, in post-mass society and now in technological society, we do not allow nature to be our limiting factor. We abstract ideas and impose them upon the land around us, and it bows to our will.

This means, however, that we are no longer able to be limited by natural laws observable in the created order. Those laws become merely obstacles to be overcome through technological mastery in order to accomplish our economic or technological ends.

This might be one reason why natural law has become forgotten in modern society, not because it truly is irrelevant, but because we can no longer see reality as it is. Nature is an apocalypsis, a revelation to us. But that clearing of nature which reveals itself has become obscured. As Heidegger worried, we can no longer see reality for what it is because we are so beclouded by what we expect nature to be: namely, in the language of Hartmut Rosa, a series of points of aggression that we must overcome and overpower for our technological ends.