Reading the Minor Prophets Means Knowing Empires

We Need to Know Assyria, Babylonia, and Persia

One feature of the Twelve Prophets is that virtually every book has a world empire in its crosshairs, or at least in its background. The partial exceptions to this rule are Hosea, Joel, and Amos. But even these turn out not to be exceptions in any strict sense.

Most of the Minor Prophets address imperial powers directly or assume them as the dominant horizon of Israel’s life.

Obadiah condemns Edom for failing to help Judah when Babylon conquered Jerusalem (Obad 10–14).

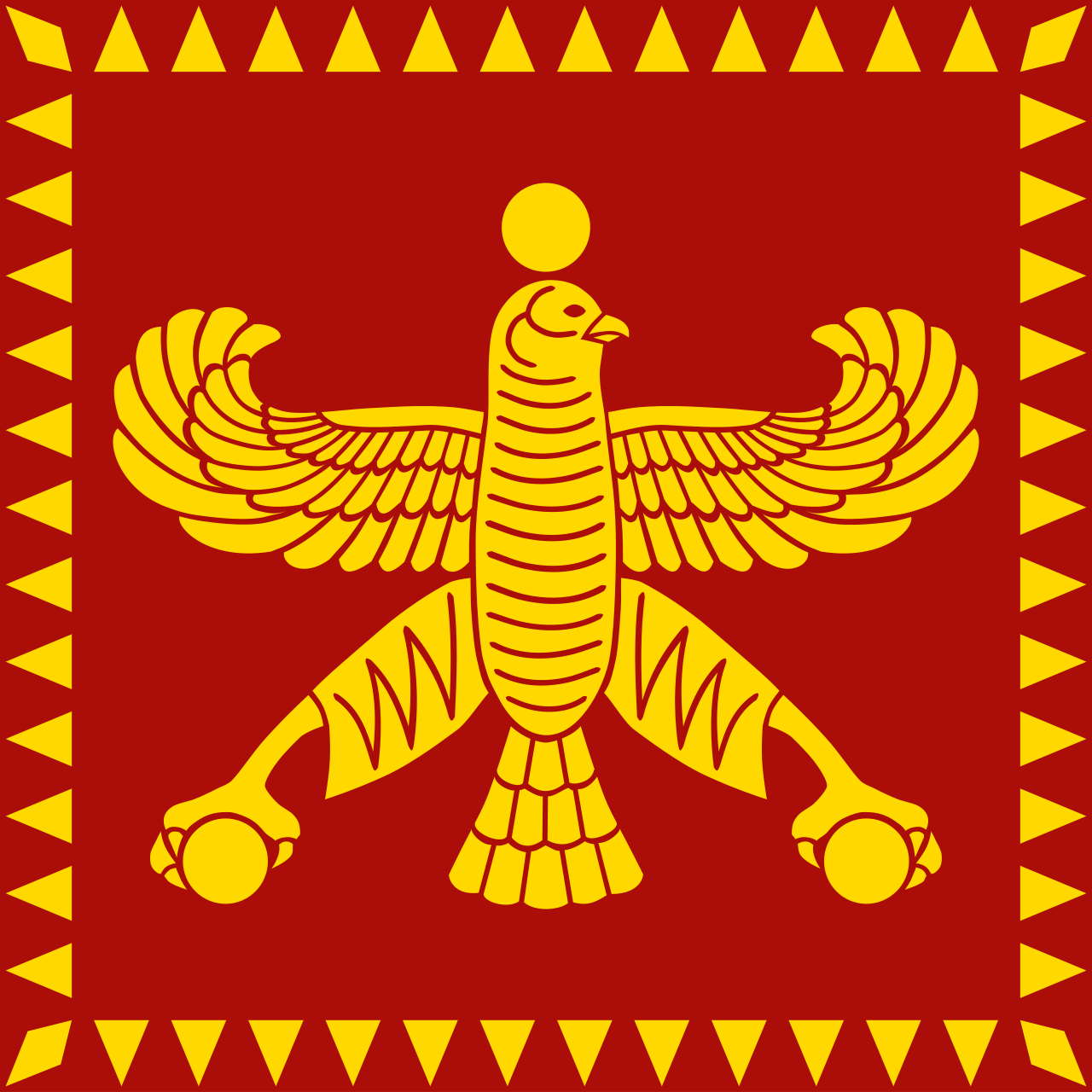

Jonah is sent to Nineveh, the capital of the great empire of Assyria.

Micah speaks against the looming threat of both Assyria and Babylon (Mic 4:10; 5:6).

Nahum is an extended oracle against Nineveh itself.

Habakkuk wrestles with God’s use of Babylon to judge Judah for her crimes (e.g., Hab 1:6, 15) and by implication Assyria.

Zephaniah points toward Nineveh’s destruction, which occurs historically in 612 BC (Zeph 2:13).

Haggai and Zechariah date their oracles according to the reign of Darius, king of Persia, under whose empire the Judahites live.

Malachi likewise portrays Judah under Persian rule, even though Persia does not appear by name.

Empire is not an incidental backdrop; it’s one of the important historical contexts for the Minor Prophets.

The “Exceptions” That Are Not Exceptions

Of the three apparent exceptions, Hosea and Amos are best understood in light of imperial absence rather than imperial irrelevance. Both address the northern kingdom of Israel during the reign of Jeroboam II (ca. 793–753 BC). Jeroboam’s success, his unusual prosperity and territorial expansion, was possible because of a temporary weakening of Assyrian power.

In the mid-eighth century, Assyria was distracted by internal instability and conflicts elsewhere. This created a window in which Israel could conduct its affairs without sustained imperial oversight or heavy tribute. Hosea and Amos speak into this moment. Their message is not triumphalist; it is accusatory. Political freedom exposes covenant failure, not divine approval.

A nation can be entirely successful outwardly but have its soul burned out. That is the situation that Hodea and Amos speak into.

A similar geopolitical pattern appears in Judah a century later. During the reign of Josiah (ca. 640–609 BC), Assyria’s power had collapsed even further, especially after the death of Ashurbanipal in 631 BC. With Assyria no longer able to enforce political control or religious pluralism in its western provinces, Josiah could implement his program of reform (ca. 622 BC), centralizing worship in Jerusalem and suppressing foreign cults that earlier Assyrian overlordship had encouraged or tolerated.

In both cases, prophetic proclamation is inseparable from imperial circumstance. A weak empire creates space for reform. Zephaniah, for example, is a prophet for reform and apparently Josiah listened. But he could do so (from a human point of view) because of Ashurbanipal’s mysterious death (just Google it, or read Assyria by Eckart Frahm).

Joel and the Problem of Dating

Joel stands apart. It mentions no empire, and its date remains notoriously difficult to establish. This silence seems intentional. As Christopher Seitz has argued, Joel functions as a theological text designed for reuse across generations rather than as a tightly dated historical oracle (argued in various ways in his Joel commentary).

Its canonical placement between Hosea and Amos is therefore significant. Joel gathers and carries forward their theological themes (judgment, repentance, cosmic upheaval) without anchoring them to a single imperial moment. The book becomes a lens through which later readers can interpret new crises under new empires.

Reading the Twelve Well

To read the Twelve Prophets well, one must read them imperially. This is not the only important historical context. It is just one of them. Even so, the Empires of Assyria, Babylonia, and Persia are not optional background knowledge; they are part of the theological grammar of the corpus. The prophets do not merely react to these empires. They interpret them, relativize them, and finally subordinate them to the covenant purposes of Israel’s God.

The Twelve or Minor Prophets only make full sense when read in such historical contexts. So go read a book on Assyria, Babylon, and Persia! Then read the Bible more skillfully than you would have otherwise!

Thanks for writing this.

Preaching through Jonah right now. Any book recommendations in this vein?