Petrus van Mastricht on Good Works: the Way to Life and Continuation of Justification

On a neglected distinction in reformed theology.

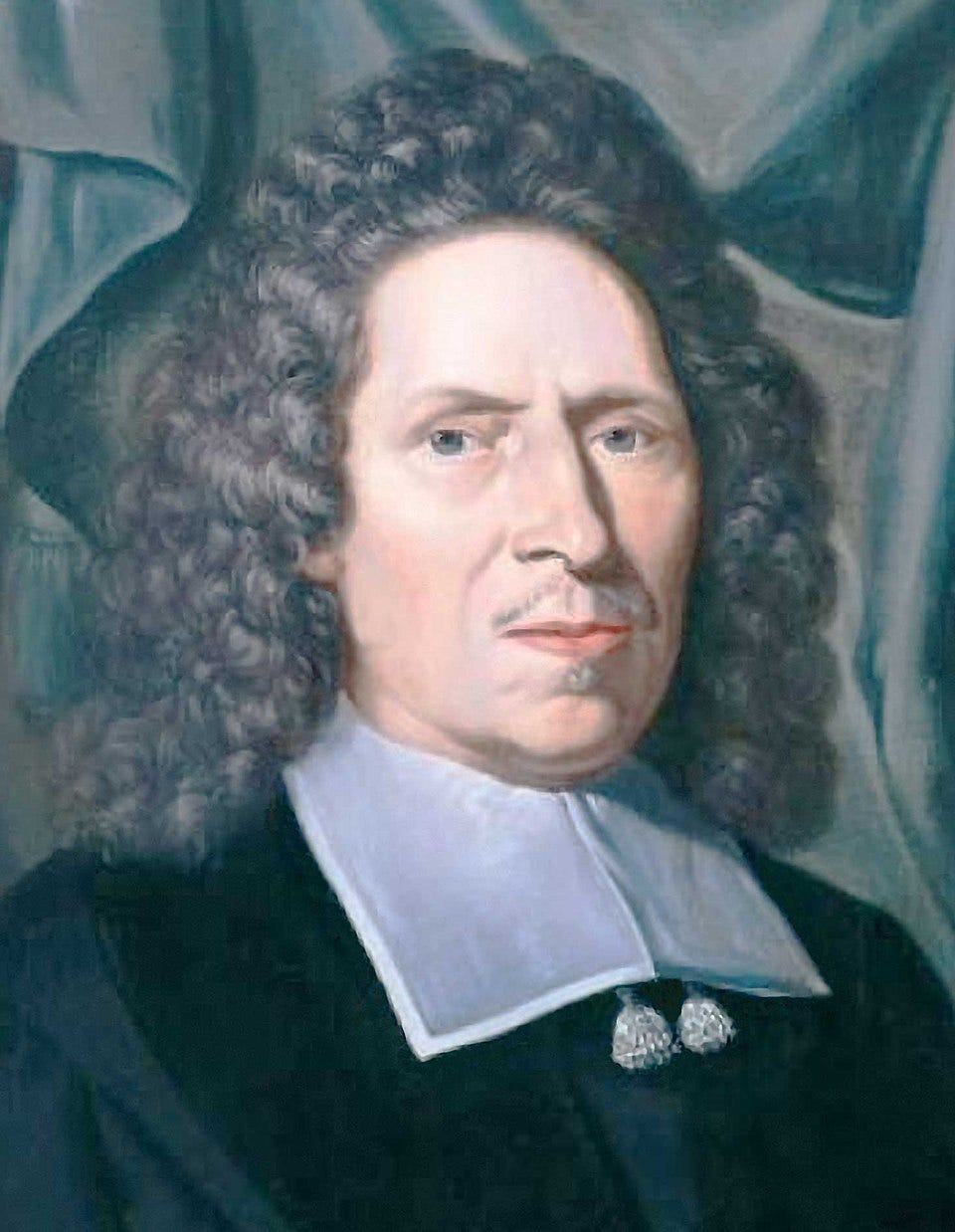

Jonathan Edwards said of Petrus van Mastricht’s Theoretical-practical Theology that it was “much better than Turretin or any other book in the world, excepting the Bible, in my opinion.” As a churchman and professor, Mastricht’s work as a Reformed theologian deeply influenced the Reformed during the 17th century and beyond.

As others of his era, Mastricht uses categories and distinctions to help us affirm all of the Bible in its textual meaning. Hence, he was not afraid to affirm that faith working through love was vital (Gal 5:6) or that James talks about a justification by works (James 2:21, 24). Rather than ignoring such passages, he was able to provide keen distinctions to help us grasp and show how such passages fit into a total biblical theology, one in which Paul also says that we are justified by faith.

Given his towering influence and ability, I want to outline his view of good works as a way to life and continuation of justification. As I surveyed elsewhere, early Reformed theologians regularly spoke of Christ’s imputed righteousness and our inherent righteousness, or good works. They affirmed that good works are necessary in the Christian life, but not as meriting our justification before the tribunal of God; but rather, as a fruit of a living faith.

Mastricht agrees and adds important distinctions as he joins authors like Anthony Burgess, David Clarkson, John Davenant, and Thomas Manton who speak about works as the continuation or condition of justification. Although such positions were normal in the 16th and 17th century, they are often neglected or even maligned today. For that reason, this article aims to inform readers about Mastricht’s representative doctrine of good works: works that do not grant the right to eternal life, but do grant the right to its possession, and that are a continuation of justification.

What Is Justification?

To begin with, Mastricht (along with the Reformed in general) affirms that God justifies us by faith alone through the imputation of the merits of Christ (§1.6.6 5:175).

In full definition, Mastricht writes:

“When God transfers the righteous sufferings and actions of Christ to our account to such a degree that we are freed from the guilt of condemnation and gain the right to eternal life. And so the justification of the guilty person who is not inherently righteous is when the fault itself of which someone is accused is acknowledged as committed, but the righteousness of the sufferings and actions of Christ is pleaded for him such that he is vindicated from the merit of condemnation. Thus all the appropriation of Christ’s righteousness depends, outside of us, upon God alone” (§1.6.6 5:175).

In other words, justification by faith means we obtain the right to eternal life not because we are inherently righteous but because God reckons Christ’s righteousness as ours. It is his, in him, and so outside of us. Besides this, justification also pardons our sins (§1.6.6, p. 5:178).

The most important distinction to remember here is that “the grace of justification excludes all human merits” but does include “the merits of Christ” (§1.6.6, p. 5:183). No good works in us can merit justification before God; only Christ’s merits can. Hence, we must have Christ’s righteousness in him imputed to us who have no meritorious righteousness in us. “Protestants,” Mastricht explains, “teach that we are justified on account of Christ’s righteousness alone” (§1.6.6, p. 5:184).

Do Justification and Sanctification Differ?

Mastricht distinguishes justification and sanctification as two forms of righteousness. The first righteousness operates concerning man, removes the guilt of sin, and “imputes another’s righteousness” (§1.6.8, p. 5:248). The second righteousness (sanctification) is in man, removes sin’s stain, and “infuses one’s own and inherent righteousness” (§1.6.8, p. 5:248).

In other words, Mastricht distinguishes between Christ’s imputed righteousness that is not our own and our inherent righteousness which is our own. This second righteousness describes God infusing holiness into us; while the first involves God imputing Christ’s righteousness to us. One is intra nos (sanctification), the other is extra nos (justification).

While Christ alone merits our justification by faith, Mastricht also argues for the necessity of good works which do not obtain “a right to eternal life,” but are “a prerequisite for the possession of eternal life (Heb 12.14), and are, as it were, the way which most certainly leads to that end (Isa. 30:21; Matt. 7:12–14)” (§1.6.8, p. 5:265).

Are Good Works Necessary?

According to Mastricht, Good works continue salvation once acquired and end in the possession of eternal life.

Mastricht connects the necessity of sanctification (inherent righteousness) to justification by faith by affirming that sanctification necessarily must exist in a believer “for the continuation of [justification] once acquired (Rev. 22:11)” (§1.6.8, p. 5:266).

By continuance of justification, Mastricht means that God has saved us for good works to walk in them on the pathway to possessing eternal life (e.g., Eph 2:10). Holiness provides “the path and leads to salvation” and “in this way from the divine pact, it provides the possession of eternal life, a reward (Matt. 5:12), a crown (2 Tim. 4:7–8), an inheritance (Matt. 25:34–35), and it is said to work ‘an exceedingly excellent eternal weight of glory’ (2 Cor. 4:17)” (§1.6.8, p. 5:266).

How Are Good Works Necessary?

They are necessary, according to Mastricht, because good works continue our justification as conditions for possessing eternal life. But note: Christ’s imputed righteousness alone merits the right to life. Good works do not merit that right, but rather they are the ordained pathway that we walk in since God saved us for good works (e.g., Eph 2:10).

Thus, while the imputation of Christ’s righteousness alone merits our justification before God, or “the right of eternal life,” Mastricht points out the Reformed “affirm that [good works] are necessary from the divine precept, in order to receive the possession of life, as conditions without which God does not will to confer to us salvation, or as Bernard said, ‘They are not the causes of reigning, but the path to the kingdom’” (§1.6.8, p. 5:273).

He continues, “The Reformed deny that [good works] are conducive for procuring justification, although they confess that they are conducive for continuing it, for making one certain of it, and for the possession of the eternal life adjudicated to us through justification” (§1.6.8, p. 5:274).

In other words, God saves us for good works, and we walk on the narrow path of life to possess life—a life that is ours by right because of the merits of Christ’s blood.

How Do Good Works and Justification Relate?

For Mastricht, the course of justification travels in three stages: its constitution, its continuation, and its consummation (§1.6.6 5:176). While God justifies us freely by grace, this does not exclude the necessary presence of good works in the continuance of justification. In his own words:

“three periods of justification should be diligently observed here, namely: (1) its constitution, wherein a person is first justified. Here is excluded not only the efficacy of good works to procure justification, but even their very presence, insofar as God justifies the sinner (Rom. 3:23) and the ungodly (Rom. 4:5).

(2) Its continuation. Here though no efficacy of good works is admitted for justification, yet their presence is required (Gal. 5:6). And in this sense perhaps, James denies that we are justified by faith alone, but requires works in addition (James 2:14, 17–18, 20–22, 24–26).

Finally, (3) its consummation, wherein the right of eternal life conferred in the first period and continued in the second is advanced also to its possession. Here, not only the presence of good works is required, but also some sort of efficacy of them, insofar at least as God does not will to confer the possession of eternal life, the right of which we already obtain by Christ’s merit alone, except, besides faith, with good works going before (Heb. 12:14; Matt. 7:21; 25:34–36; Rom. 2:7, 10).”

In other words, good works do not merit the right to life nor have any efficacy for the constitution of justification. Our justification by faith relies entirely on Christ’s righteousness, which by definition cannot be in us. It is Christ’s procured righteousness; not ours. Therefore, God imputes Christ’s righteousness in him to us, since we do not have this righteousness in us.

But good works remain necessary as to their presence, not for merit, but as the divinely appointed way to possess eternal life, which is already ours as a right by Christ’s imputed righteousness. Hence we “Strive … for the holiness without which no one will see the Lord” (Heb 12:14). And we affirm that by justification, we are new creations, “created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand, that we should walk in them” (Eph 2:10).

By walking “in them,” that is, good works, we follow the appointed path that God has prepared beforehand for us so that we might receive the possession of eternal life. So Mastricht here can take seriously the reality that “by patience in well-doing,” we must seek for glory and honor and immortality to receive “eternal life” (Rom 2:7). And while Paul will explain that we have this right to eternal life by Christ’s imputed righteousness (Rom 6:22; John 3:16), we, nevertheless, walk on a way to this eternal life by good works: “Not everyone who says to me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ will enter the kingdom of heaven, but the one who does the will of my Father who is in heaven” (Matt 7:21; also Matt 25:34–36).

Of good works and justification, Mastricht maintains that in the second stage (continuation of justification) “their coexistence is required.” He continues: “just as for the continuation of marriage a coexistence of marriage duties is required” so also are good works “because faith working through love is required (Gal. 5:6); and finally for the consummation (insofar as the possession of eternal life is pronounced), the preexistence of good works is also required for the possession of eternal life (Matt. 25:35)” (§1.6.6 5:186).

Put another way, good works do not precede justification, but they coexist with its continuance and precede its consummation (§1.6.6 5:186).

Conclusion

Whether or not we agree with this reformed doctrine of good works, we should carefully consider it. After all, this doctrine with its distinctions rebuffed the Roman Catholic view of justification and works. And justification still matters today, since it remains the doctrine upon which the church stands or falls.

Further Resources

Mark Jones on Works and the Continuation of Justification.

Wyatt Graham on whether the Reformed taught justification by works.

Wyatt Graham on imputed and inherent righteousness in early Reformed thought.

What would Mastrich or other reformed who agree on this view say about those who have fallen into sin? Should one be afraid each time they have sinned since they have fallen out of the way to possessing life? Or is it only when someone continues in sin? In other words, how would one have confidence in their justification when we often fall out of the way in our sins?

Good Protestant theologians dismiss cheap grace