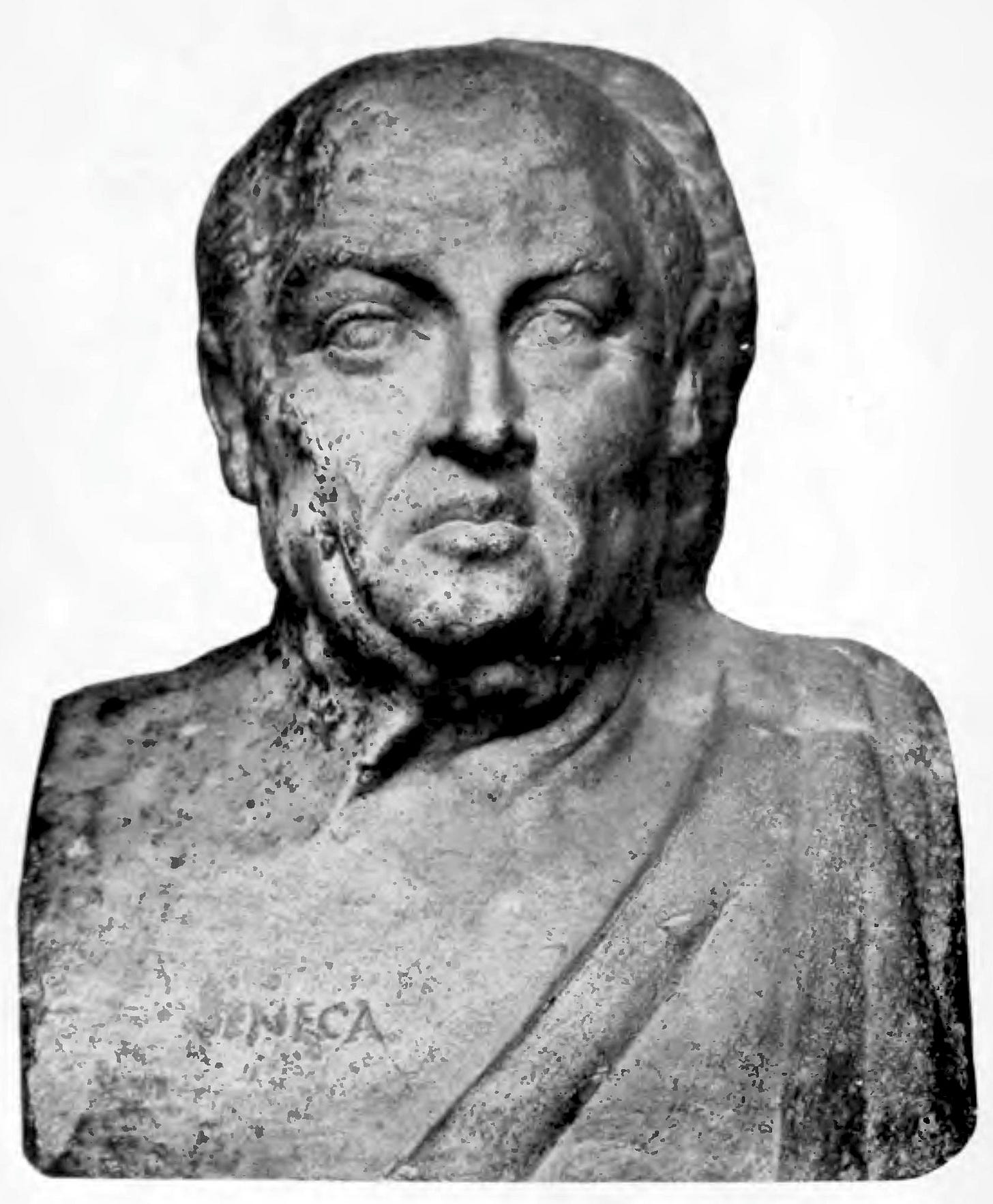

Life Is Short. So Do a Life Audit

Seneca warns us of the shortness of life. Will we meet his warning with action? Or let the future pass us by and merely exist?

Seneca calls time “the most precious commodity of all.” We often spend our weekdays waiting for the weekend, suffering “from a longing for the future” due to “a loathing of the present” (On the Shortness of Life, 7.8). We busy ourselves with work, hoping to pass the time. But that time is lost forever.

We anticipate that next year will be better. It’s only a season, we think. We imagine being free of our responsibilities in life. Soon it will be easier, we say. But by loathing the present, we lose time.

The season may not end. And life may not get easier. If we keep waiting to live, we will come to the end of it all and realize with a morbid revelation: I’ve “not lived long but long existed” (7.10).

Seneca knew this reality. He knew that even the greatest of men (even emperors) could waste their lives by hoping for an easier future. And he recognized what we often don’t: “it’s the mark of a great man, and one rising above human weakness, to allow no part of his time to be skimmed off” (8.1, 7.5).

We may have another problem, however. We may struggle to redeem the time, or even desire to remember our past, because we have wasted hours on pleasure or unproductive activities.

And so we come to a crossroads—or should come to one. What do we do now? The moment comes. It passes away. The future does not stop pulling toward you. Time is limited. What will you do?

What you must, or waste this most precious commodity of all.

You must audit your time.

Socrates said, “Now, a life unexamined is not livable for a man.”* The time of examination is now. Examine your life to make sure that you have lived and not merely “long existed.”

In his On the Shortness of Life, Seneca has helped me to understand the importance of time more than ever before. So I want to share with you what I have learned, so that you can avoid my mistakes and pursue a way of life that leads to what the ancients called the happy life.

On the Shortness of Life

Seneca wrote On the Shortness of Life to his father-in-law Pompeius Paulinus, a Roman overseer of the grain supply. As someone also involved in public life, Seneca’s goal was to encourage Paulinus to remember how short life was—and how a life preoccupied with endless details about grain or in pursuit of even greater honours often amounts to a misuse of time.

“It’s not that we have a short time to live, but that we waste much of it,” points out Seneca (1.3). We squander life, and we make it short by “soft and careless living.” When death comes, “we realize that the life which we didn’t notice passing has passed away” (1.3). And so he concludes: “the life we are given isn’t short, but we make it so” (1.4).

What makes Seneca's critique so jarring, however, is not only that he criticizes the obvious waste of time in partying and drunkenness—most agree on that. He also speaks of the busyness of certain kinds of industry, of those gripped “by the kind of diligence that busies itself with pointless enterprises” (2.1). He sees both the obvious wasting of time and the preoccupation with industry, trading, and more besides as not really living but merely passing through time.

A Wasted Life?

Why is that? It is not as simple as Seneca simply dismissing public life or industry. While writing this letter, it’s almost certain that Seneca had returned from exile (49 AD) and was engaged in public life. So he is not simpliciter criticizing regular work. Rather, he has in mind a kind of inordinate life that seeks success and busyness without reflection on what makes life worth living.

Seneca explains:

“Many are kept busy either striving after other people's wealth or complaining about their own. Many who have no consistent goal in life are thrown from one new design to another by a fickleness that is shifting, never settled, and ever dissatisfied with itself. Some have no goal at all toward which to steer their course, but death takes them by surprise as they gape and yawn. I cannot therefore doubt the truth of that seemingly oracular utterance of the greatest of poets: 'Scant is the part of life in which we live.' All the rest of existence is not living but merely time.” (2.2)

But, explains Seneca, so many people live lost in pleasure or unending busyness. While he probably unrealistically believes that people can simply choose not to be so busy, his overall point is that we become so absorbed with the things of the world that “you never thought fit to look on yourself or to listen to yourself” and thus “you were incapable of communing with yourself” (2.5).

What Seneca wants us to do is to “submit [our] life to an audit” (3.2). We must calculate how we have spent our time. Did we spend it well? “People,” explains Seneca, “trifle with the most precious commodity of all.” Because time is immaterial, we waste it freely.

But we often desire more of it at the same time! Those in public service—even emperors—desire more of it so that they can live in leisure. And we who do have it often waste it, since “the greatest waste of life lies in postponement” (9.1). We wait until tomorrow to do what we should do today.

We waste time in pleasure, busyness, and postponement. We do not use our time wisely unless we have purpose. Even good occupations in life can make us so externally directed that we never speak to ourselves, never commune with our inner self. We never take the time to become virtuous. Always in motion, never reflecting.

A Way of Life that Leads to the Happy Life

“Of all people, they alone who give their time to philosophy are at leisure, they alone really live” (14.1). Why? Because “they annex every age to their own” (14.1). Philosophy in Seneca’s time included not only traditional philosophical questions but also theological and scientific ones (by our standards). And since there already was a long tradition of such thought in Seneca’s age, his point is that we can dedicate ourselves to lives in the past and annex their time to ours, as we carry on the work of philosophy.

So we can live with a near eternity of time at our fingertips by dedicating ourselves to the past. We can thus learn a “way of living” (14.1). “Since nature,” writes Seneca, “allows us shared possession of any age, why not turn from this short and fleeting passage of time and give ourselves over completely to the past, which is measureless and eternal and shared with our betters?” (14.2)

We can find, in this narrow sense, immortality through past lives; and our life, living onward, can be annexed by others. We can dedicate ourselves to a way of life that can be called the happy life (18.4).

What exactly is the “way of living” that leads to “the happy life”? Seneca gets to the point by telling Paulinus to retire from his job of overseeing grain to enter into this mode of life:

Retire to those pursuits that are calmer, safer, and more important. Do you think it amounts to the same thing whether you're in charge of seeing that imported grain is transferred to the granaries undamaged by either the dishonesty or the carelessness of the transporters, that it doesn't absorb moisture and then get spoiled through heat, and that it corresponds to the declared weight and measure; or whether you occupy yourself with these hallowed and lofty studies, so as to learn the substance of god, his will, his general character, and his shape; what outcome awaits your soul; where nature lays us to rest upon release from our bodies; what it is that bears the weight of all the heaviest matter of this world in the center, suspends the light components above, carries fire to the highest part, and rouses the stars to their given changes of movement; and to learn other such matters in turn that are full of great wonders?

You really ought to leave ground level and turn your mind's eye to these studies. Now, while enthusiasm is still fresh, those with an active interest should progress to better things. In this mode of life much that is worth studying awaits you: the love and practice of the virtues, forgetfulness of the passions, knowledge of how to live and to die, and deep repose. (19.1–2)

Notice the primary objects of study that Seneca commends: God, our soul (including virtue and the forgetfulness of the passions), and the cosmos. Put another way, Seneca points to theology, psychology, and cosmology as the particular objects of study that point to a way of life that leads to the happy life.

Audit Your Life

Seneca does not, I should be clear, advocate for idleness. He speaks of leisure like Josef Pieper does—as the basis for society. Leisure gives us the time to pursue the most important things in life. So while we all must work, it is not in and of itself better to preoccupy ourselves with thoughtless work for our whole lives. We should also, if possible, find time to make the best use of our time.

Or else we will come to the end of our rope, only then realizing—where did the time go? We never spent the time thinking about what was good, true, or beautiful. Yes, Seneca is an elite, advocating for elitist principles. But we can see his overarching point as a sound one: audit your life, understand how you are spending your time, and use that time for the best things.

We may find ourselves as a single parent of four children. And so our time will be taken up by a job and childcare. We might despair. But remember: Seneca wrote this whole treatise while working in public political life! He shows by his actions that even in the busiest of circumstances, we can still find time to follow a way of life that leads to the happy life.

*ὁ δὲ ἀνεξέταστος βίος οὐ βιωτὸς ἀνθρώπῳ (Plato's Apology [38a5–6])