Is Tolerance Possible? Not Always.

On Herbert Marcuse’s “Repressive Tolerance”

Tolerant and civil discourse may no longer be possible in some situations. Yet as a Christian, I am convinced that we can—and must—speak with individuals to share the good news. That does not make the evangelistic task easy; potential landmines lie hidden in this evangelistic work.

One such landmine detonates upon the idea of tolerance, long assumed to be a pillar of a free and democratic society. Yet over the past decades, critical theorists have systematically challenged that assumption. As a result, tolerance itself may no longer function or even be permitted in certain situations.

In such a case, evangelism and Christian discourse may become increasingly difficult because, for many critical theorists, Christianity serves as a part of the false consciousness that enables the oppression of minorities. That is, evangelical Christianity is seen as a pillar of the Right’s power.

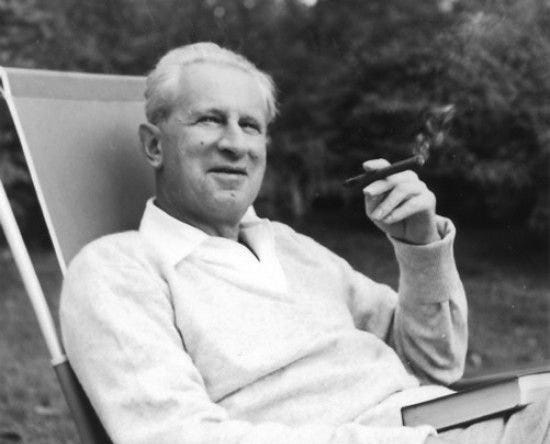

Let me explain by pointing to the work of Herbert Marcuse (1898–1979), who wrote in 1965:

“Liberating tolerance, then, would mean intolerance against movements from the Right, and toleration of movements from the Left. As to the scope of this tolerance and intolerance: . . . it would extend to the stage of action as well as of discussion and propaganda, of deed as well as of word” (Marcuse, Tolerance, 109)

For Marcuse, withdrawing tolerance from the Right could include:

Applying political violence against the Right (“self-styled conservatives,” e.g., p 107)

Withdrawing the right to free speech

Withdrawing the right to assemble

Withdrawing civil rights (110)

Censoring “word, print, and picture” (109)

Withdrawing tolerance of towards even thought and opinion (110).

And pursuing “intolerance in the opposite direction, that is, toward the self-styled conservatives, to the political Right” (110).

Restricted and controlled education (112–4)

How and why did Marcuse argue for this program of intolerance against the Right? Why did Marcuse argue for the possibility of “discriminatory tolerance on political grounds (cancellation of the liberal creed of free and equal discussion)” (106)?

That is the topic of this article. I aim to explain how critical theorists view history and its political implications. It will also show how one’s view of philosophy of history can create a social situation in which tolerance is impossible.

Why we should listen to Herbert Marcuse on tolerance

Herbert Marcuse (1898–1979) was a German philosopher who migrated to the USA, worked for the CIA (then called the Office of Strategic Services), wrote against Russian Communism, and also became the leading light of the Frankfurt School of Marxist thought. He is known as the father of the new Left.

Hence, when Marcuse writes on tolerance, we should pay attention. His influence has carried forward up to the present day, and we must face his arguments to be like the sons of Issachar who “understood the times and knew what Israel ought to do” (1 Chron 12:32).

In short, Marcuse argues that today’s tolerance is a false tolerance, one which the Left should practice intolerance towards. In his own words:

“Different opinions and “philosophies” can no longer compete peacefully for adherence and persuasion on rational grounds: the “marketplace of ideas” is organized and delimited by those who determine the national and the individual interest. In this society, for which the ideologists have proclaimed the “end of ideology,” the false consciousness has become the general consciousness—from the government down to its last objects. The small and powerless minorities which struggle against the false consciousness and its beneficiaries must be helped: their continued existence is more important than the preservation of abused rights and liberties which grant constitutional powers to those who oppress these minorities” (Tolerance, 110)

Marcuse identifies two primary problems: First, those in power use (false) tolerance to pacify the populace, who, secondly, believe the ideological lies of their rulers and thus experience “false consciousness.” Both rulers and the ruled then prop up an oppressive system that oppresses minorities.

Marcuse finds Nazism to be an apt parallel for what happens when tolerance goes unchecked in countries whose leaders are trending to the Right. He notes:

“if democratic tolerance had been withdrawn when the future leaders started their campaign, mankind would have had a chance of avoiding Auschwitz and a World War. The whole post-fascist period is one of clear and present danger. Consequently, true pacification requires the withdrawal of tolerance before the deed, at the stage of communication in word, print, and picture” (Tolerance, 109).

While such measures may only be used in extreme situations, Marcuse believes that is precisely where we are today. “I maintain that our society is in such an emergency situation, and that it has become the normal state affairs” (Tolerance, 110).

What is this extreme situation that warrants withdrawing tolerance?

First, the conditions for true tolerance have disappeared in modern democratic societies.

Following John Stuart Mill, Marcuse notes that freedom of speech and assembly (forms of tolerance) exist when the educated have authority in society. But since we neither have an educated populace nor reliable access to information because mass media obscures real information or makes horror seem a matter of course (think of a commercial running for toothpaste after a scene of war in Gaza), then we lack the conditions that make true tolerance possible.

Second, related to the first point, freedom requires a correspondence to truth, which does not exist in modern society.

Marcuse explains this connection between liberty and truth by positively citing John Stuart Mill:

“But liberalist theory had already placed an important condition on tolerance: it was ‘to apply only to human beings in the maturity of their faculties.’ John Stuart Mill does not only speak of children and minors; he elaborates: ‘Liberty, as a principle, has no application to any state of things anterior to the time when mankind have become capable of being improved by free and equal discussion.’ Anterior to that time, men may still be barbarians, and “despotism is a legitimate mode of government in dealing with barbarians, provided the end be their improvement; and the means justified by actually effecting that end.” Mill’s often-quoted words have a less familiar implication on which their meaning depends: the internal connection between liberty and truth” (86).

Since Marcuse does not believe today’s liberty is tied to truth but often sways according to propaganda, false consciousness, and the structure of society itself, he finds truth and freedom to be no longer wed together. Hence, the conditions for tolerance no longer exist.

Marcuse believes pure tolerance today impedes progress (towards freedom)

He asks, “Can the indiscriminate guaranty of political rights and liberties be repressive”? (91).

He believes so. Today’s tolerance, Marcuse avers, allows for opposition until the point of violence. But this tolerance still assumes the system of control of the oppressor class. And it also, as noted, is full of “indoctrination, manipulation, extraneous authority” (95). Further, since both our standard of living and the increase of power in the state coincide, it seems unreasonable to call attack the current system. Life is good, after all.

Yet we nevertheless find ourselves without power to effect change. And why: because in today’s free speech, nobody has a hold on the truth. All opinions are valid.

Marcuse explains, “This pure toleration of sense and nonsense is justified by the democratic argument that nobody, neither group nor individual, is in possession of the truth and capable of defining what is right and wrong, good and bad” (94).

And since information is not reliable (propaganda, control, etc.), society cannot be expected as a whole to be rational and know what is true and what is not. The power brokers control media, and thus suppress truth even when they allow “truth” to be just one idea over the others. When this happens, it feels like everyone is heard; but in reality, no one view seems true anymore.

What happens in such a circumstance? “Rational persuasion, persuasion to the opposite is all but precluded” (96). Hence, tolerance is not possible since it requires rational persuasion.

For example, Marcuse points out how political speech can make us believe a falsity, citing the Orwellian nature of propaganda. He notes (I slightly edited the below):

Thesis: we work for peace

Antithesis: we prepare for war or even wage war

Unification of opposite: “preparing for war is working for peace” (96).

With such false reason that leads to a false consciousness among people, what hope for tolerance is there? Is free speech even possible? Does it actually mean we can reason towards rational goals together? Or is it just the power of oppressors using media and ideas to achieve their goals?

“These conditions invalidate the logic of tolerance which involves the rational development of meaning and precludes the closing of meaning” (96).

Essentially, Marcuse believes tolerance in free speech is a charade in today’s democracy since the people are too easily swayed by the tools of propaganda that society itself has built. We love the oppression, and life is too good to even question it. Truth is a tool, not a goal of rational discourse.

What is behind Marcuse’s argument? In a word: Marxism

Marcuse, like most or all Marxists, pursues freedom, and in his essay on tolerance, his goal—even when he temporarily withdraws democratic tolerance—is “the restoration of freedom” (101). But some people dominate others, and those others often live under the false consciousness of their masters. Hence, a “total revolution” (102).

This revolutionary desire flows out of a Marxist philosophy of history. When Marcuse looks at oppressed class rebellions, he sees a pattern of increased freedom and justice (note the Hegelian background here):

“With all the qualifications of a hypothesis based on an ‘open’ historical record, it seems that the violence emanating from the rebellion of the oppressed classes broke the historical continuum of injustice, cruelty, and silence for a brief moment, brief but explosive enough to achieve an increase in the scope of freedom and justice, and a better and more equitable distribution of misery and oppression in a new social system—in one word: progress in civilization” (107).

He illustrates the point with various recent revolutions:

“The English civil wars, the French Revolution, the Chinese and the Cuban Revolutions may illustrate the hypothesis. In contrast, the one historical change from one social system to another, marking the beginning of a new period in civilization, which was not sparked and driven by an effective movement ‘from below,’ namely, the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West, brought about a long period of regression for long centuries, until a new, higher period of civilization was painfully born in the violence of the heretic revolts of the thirteenth century and in the peasant and laborer revolts of the fourteenth century” (108).

He makes an important contrast here: revolts of the upper classes do not generally lead to “progress” (108). Rather, it seems that only when a revolt from below occurs does real progress in civilization happen. This is because true freedom is heresy according to the ruling class—something to be stamped out because of the threat it represents.

Why don’t powerful revolutions lead to greater freedom, but the oppressed revolutions do?

Answer: Historical Materialism.

Karl Marx modified Hegel’s idea that the Idea of Freedom unfolds in history through a dialectic—a new idea replaces an older one, sublimating it, as it grows into a new stage of history.

Marx argues that the conflict that makes history progress is not one of ideas primarily, but through a dialectical relationship of classes: the oppressor and oppressed. Famously, he argued our current relation was one of bourgeoisie and proletariat.

After an early period of primitive communism, increasingly complex systems such as ancient slavery, feudalism, and capitalism create relations of production in which the owners of property use labourers to generate surplus capital.

In other words, one needs to look to the mode of production: Who owns property? Who does the labour? Who gets the surplus value? (See this helpful summary for more)

So, for Marx and other Marxists:

Who owns property? Capitalists

Who does the labour? Proletariat

Who gets the surplus value? Capitalists

The workers do not receive the full reward for their labour. They are forced to sell their time for wages, while under industrial capitalism, the capitalist owners squeeze as much profit as possible. It is an economic form of slavery, parallel to feudalism or earlier systems of bondage.

That means any historical relation between owners and labourers where the value or product of labour bypasses the labourer and goes to the owner could be seen as a form of oppression. Indeed, Marx argued that the late 19th century clearly showed this to be the case in industrial Capitalism. Remember that this was a time when workers were mistreated, children forced to labour, and the safety of workers was often ignored.

But Marcuse believes we still live in such a time in history. It is more advanced, more technologically savvy, and people are pacified through a higher quality of life. Yet we remain slave labourers to the powerful class. The greatest problem is that we do not see it, because we live under a false consciousness that tricks us into thinking we are free when, in fact, we are wage slaves.

Hence, we live in extreme circumstances that mass media and modern wealth conceal. We are oppressed like serfs or slaves, but—and this is key—we have progressed to better social relations than in the past, since history moves toward freedom through the dialectical relation of ruler and ruled. So, it is better today than in prior arrangements.

Marcuse also wrote in the 1960s, when the American Empire had imperial aspirations around the world—Vietnam, Korea, the Dominican Republic, Cambodia, Laos, and others. That empire-building has continued for some time.

But mass society has also been transformed so that, at least in the West, the conditions of factory labour are no longer so dire. Children have more rights. And one might say that the worker revolts of the 19th and 20th centuries (unions, etc.) provided this better quality of life, from a Marxist point of view.

The 21st century, however, has changed the relations of work. We still sell our labour to companies, but many now do freelance work, where we are both “owner” and “labourer,” supposedly gaining the surplus of our labour. But has this really changed the antagonistic relationship between work and reward? Are we more alienated than ever from our work?

Byung-Chul Han thinks so. He describes the technological society we have built as one marked by burnout syndrome, ADHD, and depression. Rather than our bodies being sold for labour as in the factory, he argues, we have become entrepreneurs of ourselves—of our own souls. Always working, always producing, both master and slave, predator and prey at the same time.

So if we imagine ourselves as Marxists, we might say that until this whole way of thinking changes, we will continue to be oppressed psychologically and physically. We need true freedom, and that happens only through revolution.

Preliminary Conclusion

Marcuse’s philosophy of history shapes his political approach to how we might “make history” today. As makers of history, revolutionary Marxists want us to move to the next and better stage of history to progress towards freedom as a civilization. Ultimately, they want to by revolutionary means realize freedom through re-organizing our relations of production, to make them more equal.

It is worth noting that the last paragraph of the Communist Manifesto, before the famous line “Workers of all countries, unite!”, reads:

“The Communists disdain to conceal their views and aims. They openly declare that their ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions. Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communist revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win.” (p. 32)

To succeed in this “forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions,” Marxist thinkers like Marcuse believe we must deny false tolerance where a marketplace of ideas means anyone can be right or wrong, but nothing transforms the system of oppression and repression that we live in. We need to use discriminatory tolerance, where we discriminate against the Right, conservatives. That is Marcuse’s view, which many reformational and revolutionary Marxists alike agree with.

So what then?

Christians need to be wise to the times (Matt 16:2–3). As Paul says, we must walk in wisdom towards outsiders (Col 4:5). And of course, Proverbs regularly tells us to live a life of wisdom, knowing what is and what is not.

We must recognize that we cannot persuade some people on the basis of a shared and common agreement on the usefulness of civil discourse. For some, to even engage in that discussion would mean to submit to the Right’s instrumental use of free speech to enable oppression.

Strategically, we might find ourselves freer to speak to individuals through friendship than to speak to groups of people who see us as hopelessly promoting a false consciousness.

We may also find it reasonable to analyze our time and opportunity and pursue those who are ready to hear the Gospel today. While I do not mean this in an exclusionary way, there is some wisdom in pursuing young men and women who are part of the “vibe shift.”

God will prepare hearts and guide us to opportunities. It may be that you find yourself in a haven of critical thought and are able to persuade those who listen that you are not an instrument of the Right; in which case, you may find great success. However, I do not want you to be unaware that traditional Christian views on marriage, family, and sexuality are often viewed as oppressive-class institutions. So it will not be easy.

All of this to say, Christians need to be wary about the contexts in which we live and evangelize. It may be that you try to sit down with a person or a group to speak the truth of the Gospel. But all you will hear is that religion oppresses; it is part of a false consciousness to prop up the system. Or something along those lines.

So be like the sons of Issachar, grasp the times, but then preach Christ to anyone who will listen. For a short time, that may mean you cannot reach a group of people who believe tolerance is repressive. If that happens, move on. There are more people who need Christ in the world; and let God prepare hearts for the Gospel, in his timing.