Hayao Miyazaki’s Castle in the Sky and the Limits of Technology

When technology bypasses nature’s limits, the few dominate the many

Hayao Miyazaki’s 1986 film Castle in the Sky animates Miyazaki’s ecological philosophy that would energize Miyazaki’s entire career. The film portrays a recurring pattern in human civilization that leaves us with a stark warning: when technology bypasses the limits that nature sets, power concentrates in the hands of the few, and the many suffer.

Partly because I love the film, but mostly because its argument has only grown more important in our digital age, I want to trace Miyazaki’s vision and set it alongside several Western thinkers who arrive at similar conclusions.

To Nature And Beyond

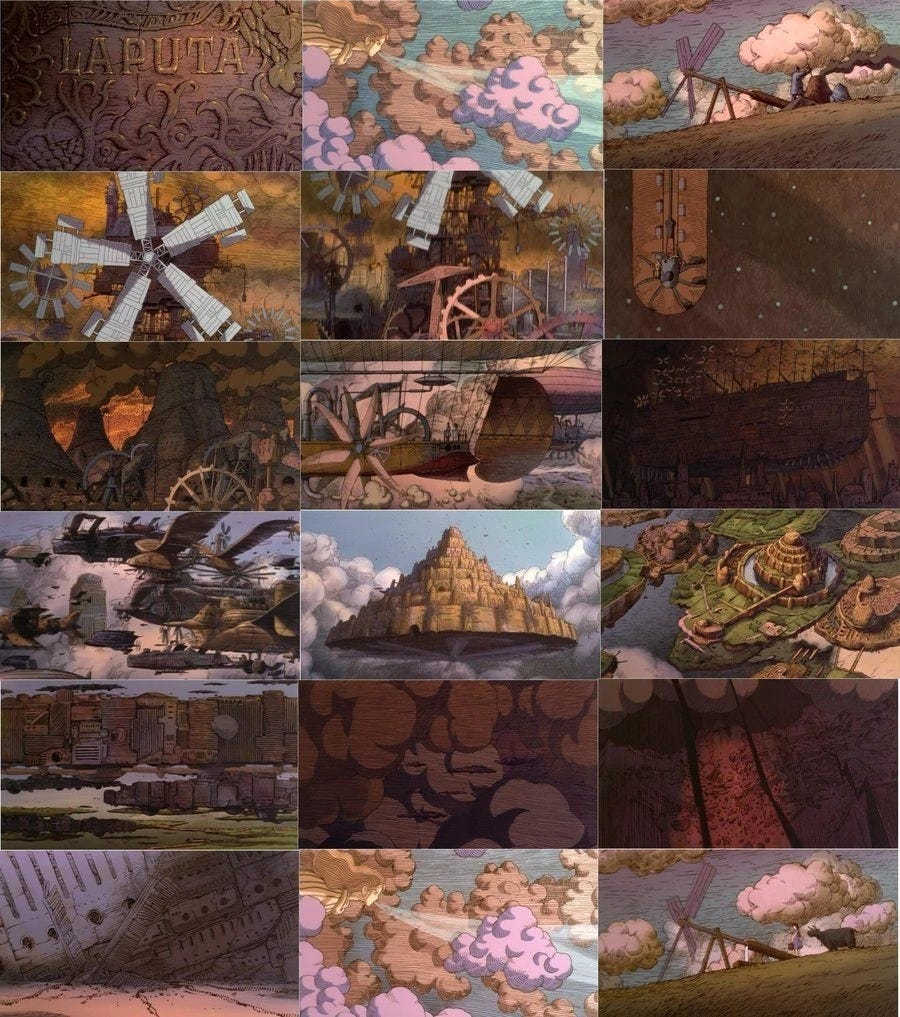

In the world of Castle in the Sky, humanity begins in an organic relationship with the earth. Wind turns windmills for grain. Boats move by sail. Houses nestle into hillsides. Technology exists, but it flows from the contours of the land rather than against them. Romano Guardini, in his Letters from Lake Como (1927), describes this kind of culture: human making that arises from attentive response to place. Guardini marvels at Italian culture, built into the rivers and valleys that they inhabit. Their technology served nature in an organic relation between human culture, making the places that humans inhabited.

Miyazaki’s opening sequences of mining towns with their windmills and sun-warmed stone render a world in transition from Guardin’s organic ideal and the coming of the industrial machine age.

In a fascinating myth of civilization, Miyazaki narrates the backstory of Laputa as a parable of technological overreach.

First, humans lived on the land with windmills and simple machines. Then they begin to dig deep into the earth and discover aetherium (called “volucite” in the Japanese original), a mineral with the power to defy gravity. They extract it in ever greater quantities and process it into crystals. At one point, they figure out that aetherium can lift them off the ground entirely. With this power, they leave the earth and build airborne cities.

At this stage, the transition is not yet catastrophic. The flying city of Laputa is built around a giant tree; gardens flourish; robots tend the flora and fauna. There is still a mixed way of life; presumably, some inhabitants favour the organic, while others favour the technological. But eventually, the royal family or others in power seize the power of aetherium, weaponize it, and use Laputa’s sky-borne position to rain destruction on the cities below. The castle becomes an instrument of domination.

Something then disrupts this regime. Perhaps it was a civil conflict, but the film never fully explains. The victors, however, choose to abandon Laputa and return to the earth. The Laputian civilization thus collapses. Seven hundred years later, the castle drifts empty among the clouds, tended only by a solitary robot who still cares for the garden, an image of technology returned to its proper, humble function.

The Abolition of Natural Limits

C. S. Lewis, in The Abolition of Man (1943), points to something similar to what Miyazaki does. What we call “man’s conquest of nature,” Lewis observes, turns out to be the power of some people over other people. The aeroplane, the radio, the contraceptive, each gives certain humans new leverage over others. Lewis warns that once we reject the objective moral order he calls the Tao, natural law, then the final stage of the conquest of nature is the conquest of human nature itself. The “Conditioners” of Lewis’s nightmare are people who have abolished the very categories of good and evil by which tyranny could be judged. (Are these Nietzsche’s Supermen? Those who have gone beyond good and evil?)

Miyazaki’s Colonel Muska is a portrait of exactly this figure. Muska exploits people and things, desires to become a god by seizing power, and wants Laputa’s technology to dominate and control the world. His contempt for the tree roots that have grown into Laputa’s throne room, his annoyance at the small bugs there, and his ambivalence to the tree at the centre of the castle illustrate his technological annihilation of man (he is the man in this case). He rejects the natural order itself. It is man overcoming man.

Resonance, Standing-Reserve, and the Loss of the World

The sociologist Hartmut Rosa names what Miyazaki animates. Rosa argues that today we want every part of the world to be reachable, available, and controllable. We want to master our environment, optimize our time, and quantify our relationships. When gain such control, Rosa says, the world falls silent. It becomes a series of “points of aggression, ”things to be managed, obstacles to be overcome. What we lose is what Rosa calls “resonance”: the experience of being called by something we cannot fully control.

The Laputians lost this resonance. From their castle in the sky, the earth below becomes a target, not a home. The wind is no longer something to work alongside, but something that can be controlled due to the power of Aetherium. The stones beneath the earth no longer mysteriously speak through their silence, but become a resource to be used, thus falling silent.

Martin Heidegger, in his 1954 essay “The Question Concerning Technology,” would call this relation to Aetherium as one of Bestand, or “standing-reserve.” When we view the Rhine River as merely a power source for hydroelectric energy, or a forest only as board-feet of lumber, we have enframed nature. We reduce it to a stockpile awaiting our use. Heidegger’s warning is that this enframing eventually encompasses human beings themselves; we too become resources to be optimized and deployed. The Laputian robots, built as caretakers, are repurposed as weapons. The people below Laputa become subjects to be dominated. Aetherium becomes muted, a power to be controlled, but lacks all mystery. The logic of standing-reserve consumes everything.

Roots in the Earth

During the film, Sheeta confronts Colonel Muska with a song from her homeland, the valley of Gondoa:

We need roots in the Earth;

Let’s live with the wind;

With seeds, make fat the winter;

With the birds, let’s sing of spring.

What makes this poem so important is that it came from descendants of ancient Laputa, those who chose to leave and return to the earth. Sheeta yearns for that return; Muska despises it. But in the end, Sheeta along with Pazu detonate the Castle in the Sky, returning the Aetherium to the ground whence it came.

When they speak the spell of destruction, Laputa’s weapons platform falls away. The Aetherium returns to the earth, but the great tree survives and lifts the garden into the sky, trailing its roots. The image is Miyazaki’s final word: nature endures even when we cease to control it.

Aetherium And Data

Miyazaki could not have foreseen the digital revolution when he made Castle in the Sky in 1986, but the pattern he identifies has repeated itself in human history. Where the Laputians extracted aetherium from the earth, we extracted oil. The Laputians processed the Aetherium into crystals, and now we turn minerals into chips for digital machines. The weapons of Laputa exist today (nuclear bombs); but while we may worry about nuclear disaster, AI and digital technology surveil us constantly, eliminating our agency, guiding our desires, and dominating us by what Byung-Chul Han calls psychopolitics.

Whenever civilizations gain new technologies, whether that be gunpowder, the steam engine, petroleum, nuclear fission, technology’s promise of freedom submits to new forms of domination. Today, our technological power regularly bypasses the limits nature sets, what Lewis calls the Tao, and makes those who wield it less humane, not more. And as Rosa would put it, the world becomes a collection of points of aggression, things to be controlled, rather than a source of resonance and genuine encounter.

A New World

Castle in the Sky animates our movement from a pre-modern use of technology to a modern, machine-like approach to technology. Whereas we used to create culture by integrating into the world as we found it, now we bypass such limits entirely. Why build a house into the side of a mountain when we can drain a swamp and build a subdivision of 1,000 of the same homes?

But as this new relation to the world advances, we begin to see a world in which the concentration of power leads to some dominating the many. Guardini saw the same pattern in the industrialization in Germany and mourned it. Lewis saw it in the ambitions of modern science. Heidegger saw it in a hydroelectric dam on the Rhine. Rosa sees it in our digitalization and optimization culture. Miyazaki sees it in a castle that forgot it needed roots in the earth.

Each of them warns us that when we bypass nature’s limits, we mute nature. We refuse to let the stones beneath the earth speak to us, resonate with us, because we have reduced them to mere supply. And thereby, we become less human.

When that happens, we lose what makes us most human and the least humane seize power and the many will suffer for it.