Don’t Get Lost in the Prophets

Four Simple Rules for Reading Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel Well

Reading the Latter Prophets can be difficult. Jeremiah, Isaiah, Ezekiel, and the twelve Minor Prophets often feel as though they come from an alien world; and, in some sense, they do. Their writings emerge from the ancient Near East, shaped by empires, prophetic callings, and social norms far removed from our own.

To help readers approach these books more wisely, I want to propose four guiding principles for reading the prophets. Many more could be added, but these four provide a solid framework, especially for reading Jeremiah, Isaiah, and Ezekiel with clarity and confidence.

First, let the book’s shape interpret its message

For example, Isaiah (13–24), Jeremiah (46–51), and Ezekiel all dedicate multiple chapters to oracles against the nations (25–32, 38–39). Where the book places these oracles communicates something important.

Ezekiel, for instance, divides his book into two time periods: before the destruction of the temple and after the destruction of the temple (Ezek 1–24; 33–48; cf. the fall announced in Ezek 24:1–14 and confirmed in 33:21). His oracles against the nations in Ezekiel 25–32 occur before the destruction, while his later oracles against Gog and Magog in chapters 38–39 testify to a future judgment that follows Israel’s restoration (Ezek 36–37) and precedes the vision of the restored temple in Ezekiel 40–48. This ordering is significant and clarifies Ezekiel’s intent.

The earlier oracles of judgment cement the idea that God is in control, even though his dwelling place (the temple) is destroyed by Babylon. His Glory had already left the temple (Ezek 8; 10; 11:22–23). And it will return (Ezek 43:1–5; cf. 40–48).

So when teaching the prophets, it makes sense to teach them in big chunks. While certainly possible to do a verse-by-verse interpretation of Isaiah 13–24, it probably makes sense to take it as a group that prepares readers for the apocalyptic vision of Isaiah 25–27.

Second, realize the topic of these books is theological

The prophets are theologians who speak of God and things related to God. Indeed, Jeremiah’s ministry focuses almost entirely on God’s word being in his mouth. As Jeremiah 1:9 says, “Then the LORD put out his hand and touched my mouth. And the LORD said to me, ‘Behold, I have put my words in your mouth.’” The rest of the book focuses on the word of God given through the prophet. It is God’s word that we must listen to.

Or consider Isaiah 40–66 and the book of Ezekiel. Both places peel back historical specificity to reveal often general or universal truths about God and things related to God. Brevard Childs comments of Ezekiel, “Often it is impossible to know whether the oracles are directed to the remnant at Jerusalem or to the exiles of Babylon. In the same way the important spatial distinctions between these two localities Babylon and Jerusalem have become entirely relativized because the people of God are viewed as one entity from the divine perspective” (Old Testament, 1979: 362).

What Childs means is that Ezekiel so prophesies from God’s perspective that space elides, since God sees his people as one despite their varied geographies.

A similar pattern occurs in Isaiah 40–66. Here, the technique of enallage (ἐναλλαγή)—and, in some cases, prosopopoeia (προσωποποιία)—allows Isaiah to shift the speaker in the middle of a prophecy without explicitly naming the speaker (e.g., Isa 41:8–10; 43:1–7; 49:1–6). This creates a sense of ambiguity that draws readers into the text and forces them to ask who is speaking and on whose behalf.

We see the interpretive effect of this intended ambiguity in Acts 8:34, when the Ethiopian eunuch asks Philip whether Isaiah 53 speaks “about himself or about someone else.” The question arises precisely because Isaiah introduces the servant’s voice without narrative clarification.

This intentional ambiguity serves Isaiah’s purpose of revealing the mystery of God’s providence and the unfolding revelation of his servant. Small wonder that Christians, once they received the prophetic key to Isaiah’s interpretation, began to call this book a “Fifth Gospel,” since it so clearly speaks of Christ. Indeed, in Luke 4:16–21, Jesus reads Isaiah 61:1–2, a passage whose speaker in Isaiah is not explicitly identified, and claims that he is the one who fulfills the oracle: “Today this Scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing.”

Such prophetic techniques reveal theological meaning in Scripture, which we must pay attention to since its authors and editors are theologians.

Third, recognize that prophetic literature interprets earlier Scripture

Prophetic literature interprets earlier Scripture, and missing that will mean missing the point of a text.

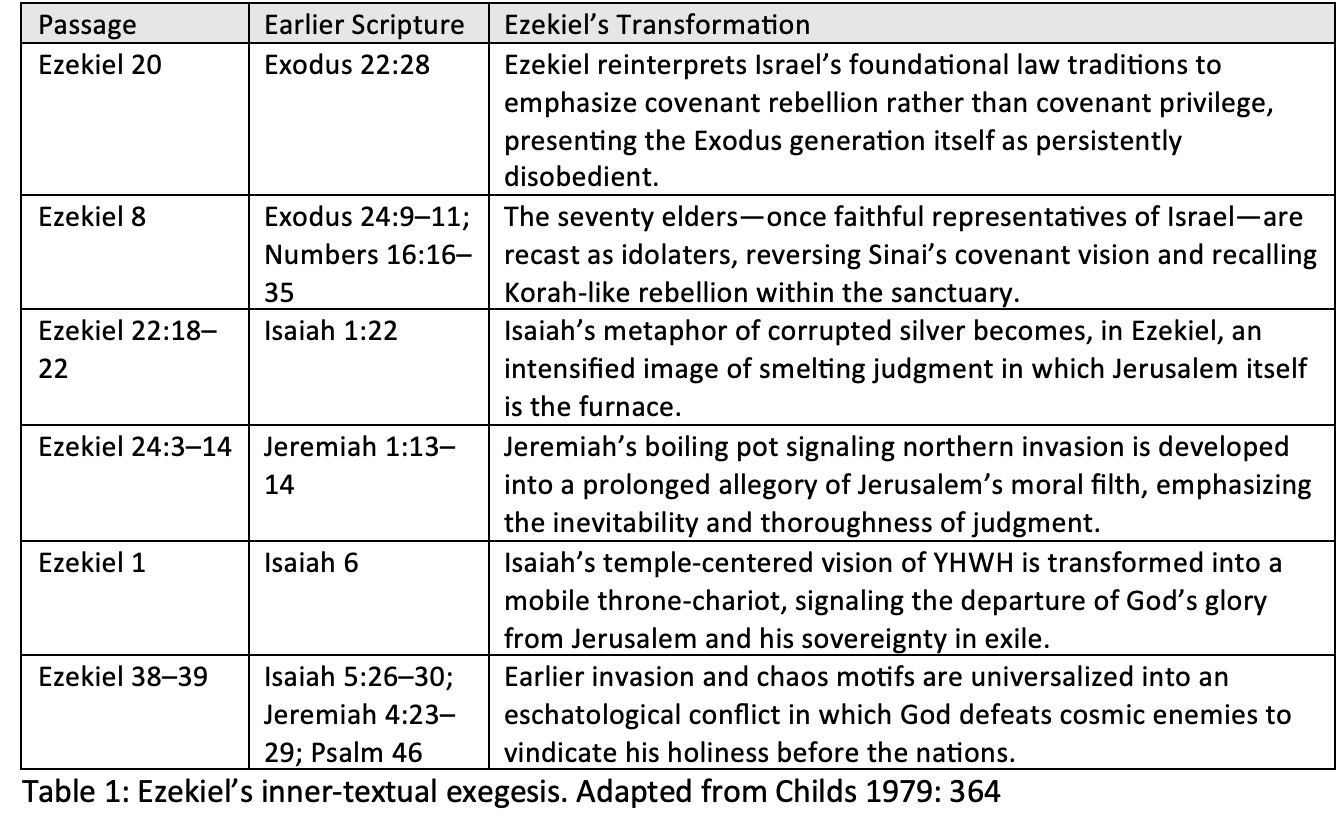

In the following table, consider how Ezekiel cites and applies earlier Scripture to his present situation:

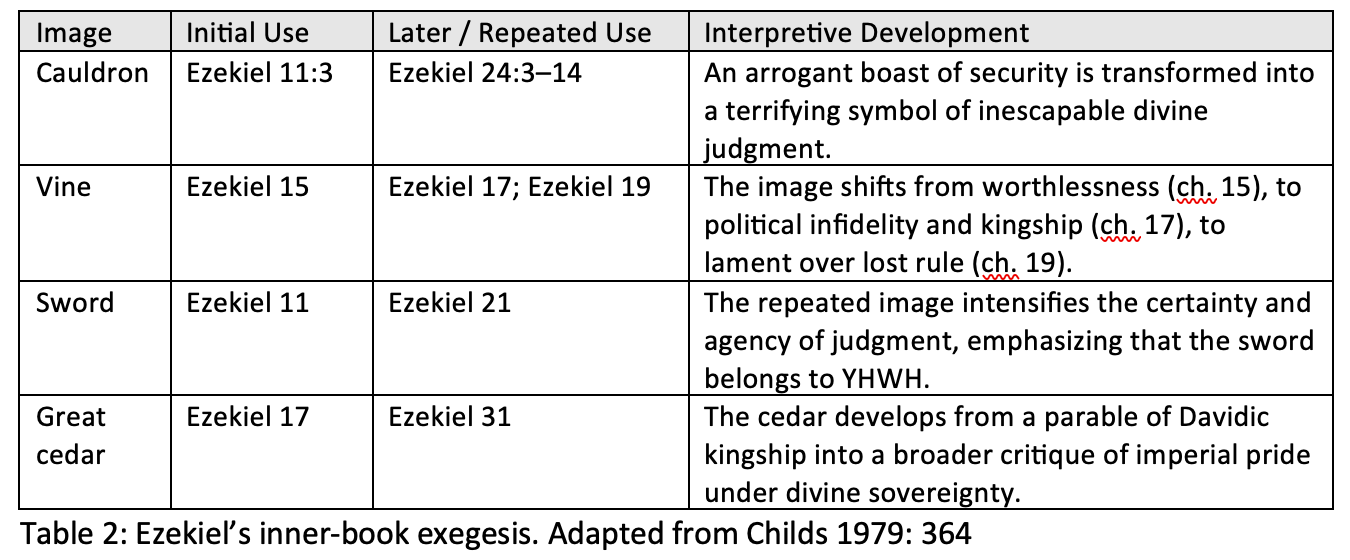

Or consider how Ezekiel draws on common symbols and pictures in the Bible or on earlier prophecies and develops them:

The point here is that to read the prophets is to read them in conversation with earlier Scripture, and in the case of Ezekiel, even with earlier prophecies in the book itelf.

By tracing these relationships, we can see how the Old Testament interprets itself.

Last, pay attention to small details

While my first point centred on the big picture, I want to zoom into the small picture here. Readers of the prophets must not ignore the trees for the forest. Sometimes we must look at the individual pine needles to see something quite wonderful.

For example, compare the translation of Isaiah 53:11 in the ESV and NIV:

ESV: Out of the anguish of his soul he shall see and be satisfied. By his knowledge the righteous one, my servant, shall make many to be accounted righteous, and he shall bear their iniquities.

NIV: After he has suffered, he will see the light of life and be satisfied. By his knowledge my righteous servant will justify many, and he will bear their iniquities.

The ESV and NIV have certain stylistic differences, but there is one major difference in content. The NIV completes the direct object of “see” with “the light of life,” a phrase that, in light of Christ, would suggest his resurrection from the dead: “After he has suffered.”

So what is going on here? In answer to that question, we have to discuss certain details of the underlying text.

First, the ESV uses the Masoretic Text as its base text for translation. The Masoretic Text is a Hebrew textual tradition whose earliest complete manuscripts are medieval, yet which faithfully transmit a much older textual tradition, most notably preserved in the Aleppo Codex (c. AD 930) and the Leningrad Codex (AD 1008), the latter of which serves as the primary base manuscript for modern critical editions of the Hebrew Bible such as Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia and Biblia Hebraica Quinta.

However, while these texts are stable, the earliest complete Masoretic manuscripts are relatively late in comparison with some early Greek versions and the Dead Sea Scrolls. So the Göttingen edition of the Septuagint (ancient Greek translation) translates Isaiah 53:11 in this way:

LXX Isa 53:10b–11: καὶ βούλεται κύριος ἀφελεῖν ἀπὸ τοῦ πόνου τῆς ψυχῆς αὐτοῦ, δεῖξαι αὐτῷ φῶς καὶ πλάσαι τῇ συνέσει, δικαιῶσαι δίκαιον εὖ δουλεύοντα πολλοῖς, καὶ τὰς ἁμαρτίας αὐτῶν αὐτὸς ἀνοίσει

Translation: And the Lord wills to take away from the pain of his soul, that is, to show him light and to shape his understanding, to justify the Righteous one who serves many well—and he himself will bear their sins.

Now, the Septuagint is not alone in this rendering. At least two Dead Sea scrolls agree with the “light” reading as, for example, 1QIsa a reads:

מעמל נפשוה יראה אור וישבע ובדעתו יצדיק צדיק עבדי לרבים ועוונותם הואה יסבול

Translation: From the pain of his soul, he will see the light, and he will be satisfied; and by his knowledge, the Righteous one, my servant, will justify many; and he will bear their sins.

Now both 1QIsaa and 1QIsab share this reading, and so it is not unique. Both texts therefore represent a textual tradition of Isaiah 53:11 from before the first century.

They, like many ancient Greek Versions, agree that the servant will see the light after suffering. Both ancient texts further emphasize that this light imparts a kind of knowledge or understanding upon the servant that allows him to be justified or justify many. In any case, he can give gifts to them as Isaiah 53:12 says.

Now, one difference here between these versions of the Masoretic Text is the emphasis on seeing light after suffering. For my part, I suspect that the Masoretic Text may have chosen to preserve a text type that did not support Christian exegesis, given its medieval provenance. Hence, I tend to see the NIV as a better or more ancient reading, albeit I understand that there are many complications here.

Textual criticism is not for the faint of heart.

But I draw all of this out simply to note that sometimes we need to drill down into a text to understand its full meaning. Sometimes one pine needle clarifies the lay of the whole forest.

Conclusion

Reading the Latter Prophets requires patience and care. These books must be read as wholes, with attention to their theological focus, their use of earlier Scripture, and even their smallest details. When we attend to a book’s structure, listen to God’s voice, trace how Scripture interprets Scripture, and slow down to notice key textual features, the prophets become far less alien. Instead, they reveal profound witness to God’s purposes in history, purposes that ultimately find their fulfillment in Christ.

If you want to learn more about the prophets, you can audit my class on how to read the Old Testament as Christian Scripture by clicking the button below. It’s only $299 CAD to audit.

Thanks, Wyatt, for your thoughtful article.

I have not delved into the Prophets yet, so appreciate this post. I also like your textual analysis and comparison of ESV and NIV. I know textual analysis is all very complex, yet I’ve found myself returning to the NIV this year. This is partially due to some lingering aftermath from a spiritual abuse experience (where only certain versions were allowed to be read), and partly because I find ESV feels wooden and NIV feels more heartfelt.