Augustine's Hermeneutics of Love

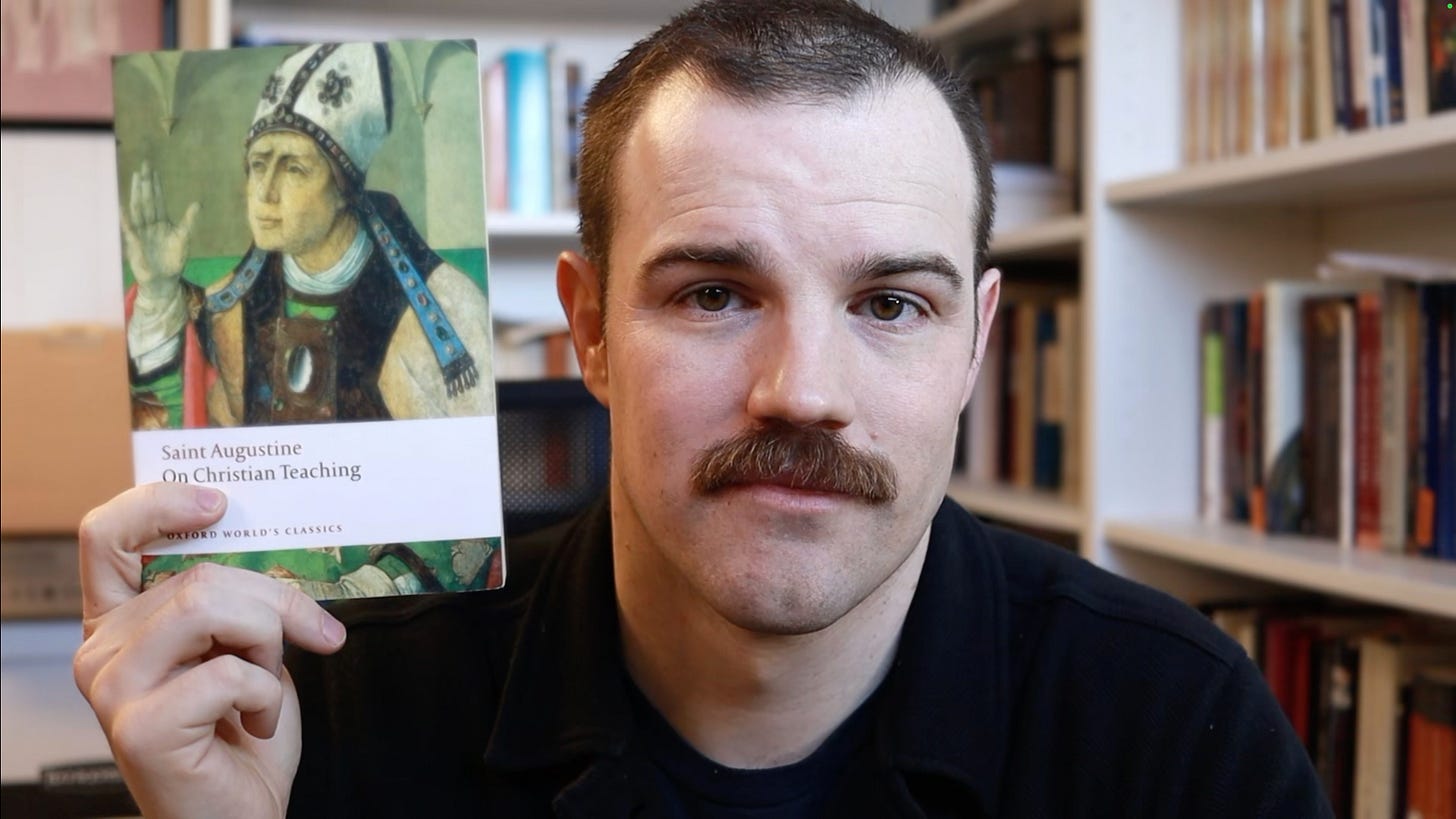

In "On Christian Teaching," Augustine shows us how things in Scripture and the world are meant to be used for God's sake, for finding our ultimate pleasure in God.

Augustine’s On Christian Teaching presents a hermeneutical theory whose ultimate aim is not merely to inform the mind with facts but to transform the reader through rightly ordered love. Understanding his approach requires grasping his foundational distinction between signs and things, and between use and enjoyment.

Signs and things

In Book One, Augustine develops what initially appears to be a complicated theory of signs and things, though on reflection it proves quite straightforward. When we read Scripture or interpret the world around us, we encounter signs (words, for instance) that signify things. The word “tabernacle” brings to mind a tent; the word “temple” evokes a temple. So far, so simple.

The key move comes when Augustine distinguishes between how we should relate to created things. Everything in this world can either be used or enjoyed. The problem arises when we attempt to find ultimate pleasure in created things, as though they could fully satisfy our deepest needs. Created things are by definition changeable, malleable, and corruptible. Moth consumes them; rust corrodes them. Whatever pleasure they offer is temporary and transient, liable to be lost.

By contrast, there exists something or rather, Someone who is eternal, immutable, and unchanging: God himself. We are made to find ultimate pleasure in him. Augustine does not deny that we naturally take pleasure in food, friendship, and the goods of this life. His argument is rather that if we treat such things as finally pleasurable, whether sex, money, or any other created good, they will prove enjoyable for a time but ultimately disappoint. This was Augustine’s own experience, recounted throughout the Confessions.

Use and enjoyment

The proper response, then, is to regard created things as useful, not in a merely instrumental sense, but as goods that draw us toward ultimate pleasure in God. We do all things for God’s sake: whether we eat or drink, as the Apostle Paul says, we do all for the glory of God. In Augustine’s framework, we swim for God’s sake, eat for God’s sake, love for God’s sake. This reorients our vision so that we see the things of this world not as ends in themselves but as means toward our ultimate end, which is God.

This need not involve constant conscious reflection. One does not pick up a fork thinking, “This utensil is useful for my enjoyment of God.” Rather, Augustine is describing the ontological reality of created goods: they are what they are, regardless of whether we attend to this truth in every moment. Friendship, beauty, and earthly joys remain genuinely good—but they are goods that, upon reflection, draw us higher still.

This distinction proves essential for hermeneutics. When interpreting Scripture and the world, we must recognize the difference between God, who alone is to be enjoyed as our final end, and created things, which are useful for bringing us to the God who gives us that final pleasure.

The restless heart

Augustine learned this lesson through his own restless searching, as he recounts in the Confessions. For him, everything comes back to love and the heart. God made us for himself, and consequently our hearts are restless until they find rest in him.

Why should this be so? Return to the theory of things. Created realities are changeable, losable, corruptible, temporary and transient. If the heart fixes itself upon such things, it will be just as stable as they are. Which is to say: the heart will become temporary, transient, unstable, ready to be consumed by the same forces that erode all earthly goods. Such a person will not be like a rock against which waves crash harmlessly but like the water itself, scattering in every direction upon impact. Augustine knew this instability firsthand.

Purification of the heart

How, then, does one move through this problem? When interpreting Scripture and the world, we must recognise created things for what they are and what they are for. We treat them as useful, good, and genuinely joy-bringing but for God’s sake, as means of drawing us to him.

Augustine develops this through the biblical language of purification. Paul prays that the eyes of the Ephesians’ hearts might be enlightened (Eph. 1:18); Jesus declares that the pure in heart shall see God (Matt. 5:8); Peter in Acts speaks of God purifying hearts by faith (Acts 15:9).

Our hearts, the invisible aspect of ourselves capable of perceiving the invisible God, are somehow obscured by our bodily appetites, which incline us toward pleasure in created things. We must be trained to love rightly, to see earthly goods as drawing us upward to God. In his On the Trinity, Augustine traces out this process of purification through contemplating the eternal God in contrast to temporal, created things that are good but not meant to satisfy us ultimately.

The goal of Scripture

To summarise Augustine’s hermeneutical theory: when reading Scripture or interpreting the signs of the world around us, we should see them not as ultimate goods but as things useful for drawing us to God, who made us for himself and made us to find ultimate pleasure in worshipping him. This is how we attain the deepest happiness available to us.

The goal of Scripture, for Augustine, corresponds to Jesus’s summary of the law: the whole law hangs upon love of God and love of neighbour. Love fulfils the law. We are to love the Lord our God with our whole heart, soul, and mind by purifying our minds to understand what things truly are so that we may love our neighbours as those worthy of love for God’s sake. Our neighbours bear intrinsic worth as God’s image-bearers, yet our love for them ultimately directs us toward God himself.

This is why Augustine can say that even if we err on certain details of interpretation, we may still have grasped the main point if our reading encourages love of God and neighbour. He is not commending inaccuracy; his point is that Scripture exists to lead us to love. We will inevitably make mistakes (that is simply part of being human), but we must not miss the central aim. Created things are good and useful, useful precisely because they draw us from changeable realities toward the one unchanging reality: God himself.

Conclusion

Augustine’s hermeneutical vision, articulated in On Christian Teaching and throughout his writings, insists that reading Scripture and interpreting the world is not merely an intellectual exercise aimed at accumulating facts. It is a transformative process whereby rightly ordered love enables us to see everything as a theatre of God’s love, mercy, and glory; these are things to be used for God’s sake, that we might worship him and find our ultimate pleasure in him alone.

Brilliant breakdown of Augustine's use/enjoyment framework. The part about how created goods remain genuinely good but must point higher really clarifies the trap of treating anythng as a final end. I tried applying this to social media last year and it totally reshaped how I engage with platforms, less dopamine chasing, more intentional connection routed back to teh bigger picture.

Thank you Wyatt for expanding on Augustine’s hermeneutical of love in this Substack.

My dissertation was also on this topic as I explored the value of Augustine’s hermeneutic as an epistemology.

https://a.co/d/dofGxWE